The thriller gets off to a good start with the title. Any China–Taiwan story without “dragon” or similar Orientalist cheese in the name is a welcome reprieve from the likes of Dragon Teeth, Dragon Storm, and Operation Red Dragon. Having a dragon-free title is a minor point perhaps, but it’s indicative of the lack of Asian clichés in the novel. With this genre, there’s usually a white male protagonist (a character for the Western reader to identify with) and a local love interest (a svelte beauty with a name like Jade Dragon) who unveils for the hero the mysterious ways of the East. In contrast, all the characters in The Sons of the Republic are either Taiwanese or Chinese, and there’s no romance. Instead, we get straight narrative with just enough explanation, courtesy of author J.W. Henley’s clever choice of main character, Jason Su, a wealthy young Taiwanese businessman who grew up in the United States.

The story opens with a mysterious dead body found floating alongside a Taiwanese naval vessel in Kinmen, Taiwan’s frontline island fortress just kilometers from the Chinese coast. Jason and private investigator Li-Yang, a lanky six-foot-five alcoholic hard man, are drawn into a deadly hunt for the killer, with the layers of intrigue taking us from encounters with two-bit gangsters and corrupt cops to the corridors of power.

Sons of the Republic explores the blurred intersection of crime, politics, and money in the PRC–ROC standoff. With no clear-cut good guys, we’re kept wondering who is working for whom, and to what end. As the intrigue deepens, we realize the fate of Taiwan’s sovereignty hangs in the balance.

Originally from Saskatoon, Canada, Henley now calls Taipei home, and is known to many fellow expats as a metal/punk musician and for his coverage of the local music scene in the Taipei Times. After graduating with a degree in journalism in 2005, he came to Taiwan and worked for an academic publisher producing ESL materials. He gradually built up his freelance writing channels, and was able to quit his job. Newly freed from fulltime ESL drudgery and spurred on by turning thirty, Henley threw himself into writing Sons of the Republic and just a few months later had a first draft — an intensity of effort reflected in the novel’s punch and cohesiveness.

Given the thirstiness of the characters and the inclusion of several superfluous descriptions of hangovers, I suspect that there was also a fair amount of drinking done during that time. It has to be said, though, that the drinking passages are pitch perfect, whether they are of alcoholics drowning their sorrows in low-rent booze joints or high-rollers in swanky upmarket bars. Henley’s depictions of violence are excellent, too. In one scene, Jason and Li-Yang are trying to beat some information out of a Chinese agent called Tung.

“Do it.” Tung remained defiant. “Make me a martyr, and seal your fate as dead men.” His voice gurgled as he choked on blood spilling from his mangled mouth into his throat, his remaining teeth stained dark red. He swallowed it back, seeming to relish the copper taste of gore, tipping his head backward to let it drain down into his stomach. If these were to be his last words, he wanted them clear. “Pull the fucking trigger.”

A shot so loud it threatened to crack the walls rang out and blood and bone sprayed from Tung’s left kneecap. A horrid shriek flew out of his mouth like a crazed banshee bent on liquefying crystal with its piercing tones of anguish. Li-Yang spun round to see Jason holding a smoking gun, still aimed at Tung, held in the exact position in which he had squeezed off the shot. His arm was rigid steel, his eyes wide. Li-Yang had rarely seen him with so much as a hair out of place. Now, a madman with a gun stood before him—a lunatic pushed over the edge.

One of the reasons Sons of the Republic reads so well is that it has just the right number of characters — enough to add color and complexity but not so many as to confuse – and it also has them distinctively named. An all-Asian cast often turns a story into an alphabet soup of Chang, Chen, Cheng, and Ching, and you soon lose track of who is doing what. Henley uses different-sounding names, nicknames, and titles to avoid any confusion.

Most expat fiction has at best mediocre prose and plotting, along with an overuse of iconic locations that turns the story into a tourist romp defused of narrative tension. Sons of the Republic, however, has a lean, exciting story. I enjoyed revisiting familiar settings but was pleased that the book emphasizes action and suspense — think modern film noir rather than an indulgent location shoot. Although Sons of the Republic would have benefitted from an editorial trim here and there, it’s an impressive debut. I read it because it was recommended to me, and I’m passing that recommendation forward in the hope that the novel gets the word-of-mouth it deserves.

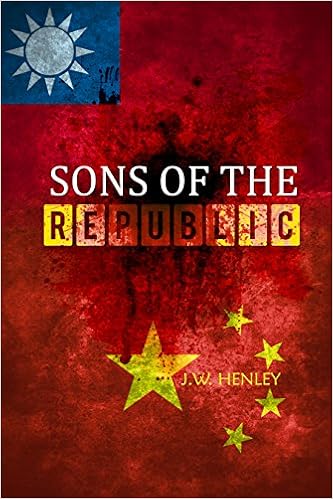

Sons of the Republic (Library Tales Publishing, 2014)

Also available on Amazon