Between the time when the Maoist stranglehold loosened and the rise of the globalized Internet-connected China, there was an age of undreamed-of possibilities. And unto this came American musician Dennis Rea like a time traveller from the future, guitar in hand, bearing the dubious gifts of progressive rock and free jazz. From obscurity to accidental rock demi-god, his days of musical high adventure are chronicled in the most excellent Live at the Forbidden City.

When Rea first arrived in China in January 1989, the 31-year-old Seattle-based musician was just tagging along. His fiancée, Anne Joiner, had landed a job teaching English at a university in Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan province. Rea also obtained a English teaching job at the school and the couple lived together on-campus.

Rea quickly became involved in the burgeoning music scene. Local musicians were hungry to learn about Western music and Rea found himself in great demand as a guitar teacher and performer. During his fifteen-month stay in China he was invited to increasingly large concerts and high-profile radio and television appearances, played with some of the biggest stars in China, and recorded a bestselling album. He writes: “I had somehow stumbled into the role of musical ambassador, introducing impossibly vast audiences to jazz, art rock, and other novel foreign musical genres.”

China was virgin territory in those days – and with the resultant opportunities – but it was an extremely hard place in which to live, work, and travel. Rea generally plays down the discomforts, with few mentions of the staring, spitting, shoving, and disgusting toilets that used to make the country such an ordeal. Still, we get a good sense of the everyday hardship endured from this passage:

Wintertime was especially trying. To conserve money and resources, the Chinese government had decreed that public buildings in southern China go without central heating despite the penetrating midwinter chill. This meant playing shows in subfreezing temperatures, cocooned in a half-dozen sweaters and exhaling billows of breath vapor. Playing an instrument well demands a certain degree of digital dexterity even under the best of circumstances, but in Chengdu the biting cold all but crippled my fingers, making it devilishly difficult to get through even the simplest musical numbers. I took to furiously rubbing my hands together, burying them in my pockets or armpits, gripping cups of hot tea to the point of pain, and even running laps around the building before taking the stage.

As well as being an interesting read, Rea’s account is also of some historical importance; he was a rare Western witness to the brutal crackdown of protesters in Chengdu in 1989, and his account a reminder that the 1989 democracy movement was a national phenomenon, not something limited to Beijing. As in other cities, it was the death of political reformer Hu Yaobang in mid-April which brought student protests to the streets of Chengdu. Mirroring what was unfolding in Tiananmen, the students occupied Tianfu Square, camping at the base of its towering Mao statue.

By late May, however, protests had lost momentum and things were expected to return to normal. The few remaining protesters were cleared from the square on the morning of June 4th, but on hearing of the bloodshed in Beijing, people once more poured into the streets. The police moved in with tear gas and batons: pitched battles ensued.

Rea and Anne, accompanied by another American and an Italian, cycled into town. A t a small hospital near Tianfu Square they “watched in horror as volunteers hauled a steady stream of bloodied victims into the clinic on stretchers, vendors’ carts, bicycles, and other makeshift conveyances.”

A doctor implored them to come in and take photographs of the victims. Judging from the numerous head injuries, it seemed the police had intentionally trying to inflict maximum damage. The one actual killing Rea witnessed firsthand during the chaotic three-day suppression in Chengdu, however, was of a policeman in the hospital.

“A few minutes later a carelessly disguised policeman tried to enter the hospital. The infuriated crowd sniffed him out at once and fell on him like a flock of buzzards, brutally stomping the life out of him right before our eyes.”

Rea’s account of the crackdown in Chengdu seems like an even-handed one; seeing the brutal murder of the policeman at such close range no doubt discouraged any overly sentimental and partisan take on the carnage.

Most of the foreign teachers “decided to bail out of the country the next day aboard hastily chartered flights” but Rea and Anne stayed on. As such, they found themselves occasionally used for propaganda purposes, Rea and fellow laowai shown on television at a banquet with officials as “brave foreign friends who stayed through the counterrevolutionary rebellion to show their support for the government’s policies.”

Live at the Forbidden City has fascinating up-close and candid profiles of China’s rock star royalty. I especially enjoyed reading about rock pioneer Cui Jian, whose music was part of the soundtrack to China in the late 1980s and his song “Nothing to My Name” an unofficial anthem for the disaffected youth of the Tiananmen generation.

After Rea’s year at the university was up, he stayed on for several months doing various musical projects, and then moved to the southern Taiwanese city of Tainan, where he taught English, only this time earning as much in a day as he had in a month in Chengdu. As well as playing in various bands in Tainan, he managed to use his new China connections to organize two tours of China (one with a Taiwan expat band and another with musicians from Seattle).

Live at the Forbidden City is a bittersweet book – alongside the funny anecdotes and lighter travel passages are the sad events of June 1989 and in the later chapters the unfulfilled hopes of China’s music scene: “what appeared to be the genesis of a truly revolutionary cultural movement” became over time a spent force for social and political change, increasingly commercial, hierarchal, narcissistic, and tame.

Referencing Cui Jian, Rea says:

… no noteworthy figure has arisen to assume his place as the face of defiance. Indeed, one can now find Chinese rock bands that take a hardcore pro-government stance, as exemplified in a performance video that went viral during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, in which the local punk band Ordnance bellows at a mixed Chinese and foreign audience, amid a welter of coruscating distortion, “The Olympics have brought a lot of people here from outside the country. We should tell them, Taiwan is OURS!!!Tibet is OURS!!! Overheated nationalism rules the day.

Speaking of politics, there were – for me at least – a few throwaway left-wing lines in the book that irked. Christian missionaries teaching English at the university are predictably described in a dismissive fashion. And of his move back to the United States in 1993, Rea writes: “Thankfully, we had missed the entire presidency of the sinister Bush I.” Dear me, such blindness to the irony here of his missing the “sinister” Bush senior from having chosen to spend time in a repressive shithole like China, working with the authorities and being used at times as a propaganda tool. (And even Taiwan, despite undergoing democratization had not then had its first presidential election).

Still, I really enjoyed the book, and that’s not a bad recommendation coming from someone who has little interest in and seldom listens to music of any kind, let alone alternative strains. Live at the Forbidden City is a fascinating story of a man in the right place at a special time. The author’s own assessment of his story is an accurate one:

My experience as an emissary of alien music to millions of Chinese can never be repeated in quite the same way, by myself or anyone else. I showed up with guitar in hand at just the right time and place, in the waning days of a period of musical openness and innocence that has since vanished forever in China’s headlong rush toward modernity.

Live at the Forbidden City: Musical Encounters in China and Taiwan is published by Blue Ear Books and also available on Amazon.

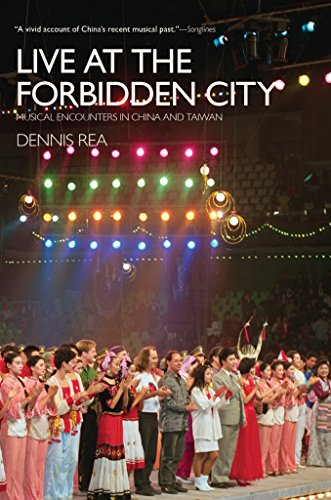

(Photo from Rea’s Wikipedia entry, taken by Anne Joiner)

(Photo from Rea’s Wikipedia entry, taken by Anne Joiner)