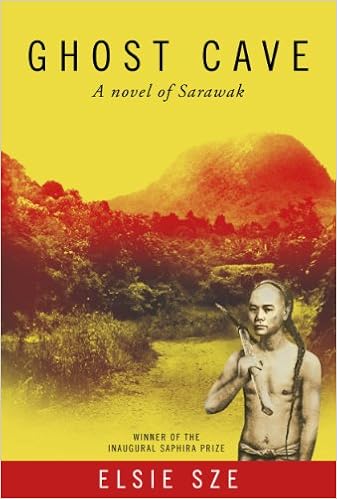

Borneo. Few place names are more evocative of old-style adventure. Steamy jungles, headhunting Dayaks, exotic wildlife, and scantily clad native women – the stuff that schoolboy dreams are made of. And the most romantic of all was Sarawak, in northwestern Borneo, a kingdom ruled by a dynastic monarchy of Englishmen from 1842 to 1946. The first of the white rajahs was James Brooke, granted the territory by the sultan of Brunei for his military assistance in quelling rebellion and combating piracy. It’s a hopelessly seductive story – basically a Kiplingesque “The Man Who Would Be King” fantasy for those who prefer hot weather – and not surprisingly the basis of numerous fiction and nonfiction accounts. Elsie Sze’s Ghost Cave takes us to the Sarawak of James Brooke’s time but instead tells the story of Chinese migrants and their interaction with the indigenous Bidayuh people.

Ghost Cave is a multigenerational family saga that starts with Therese, a Canadian-born Chinese, arriving in Kuching, Sarawak. She’s there to interview her grandfather about fighting with communist insurgents in the 1960s, as part of her research for a master’s thesis, yet she ends up unravelling far more family history than bargained for.

Therese is given a journal that tells the story of her grandfather’s great grandfather, a young Hakka man called Ah Min. The journal, which forms the heart of the novel, describes how Ah Min and his good friend Lo Tai leave impoverished Guangdong in southern China in 1849 to find their fortune in Sarawak.

After a long and gruelling voyage, the two friends step ashore in Kuching:

This then was the town Ah Min and Lo Tai had come to. Its oppressive tropical humidity and intense heat made their hot and sticky summers in southern China seem like a cool paradise. From the <em>Nam Wah</em>, Ah Min and Lo Tai took a sampan ashore to the waterfront, which was lined with a row of two-storey shophouses facing the river and referred to by the locals as the Main Bazaar. The smell of rotting fish and fruit, and stale human sweat, assailed their nostrils as they stepped onto the jetty. After so many weeks at sea the stench was almost overpowering. Leaving Ah Min to watch their belongings by the pier, Lo Tai went off on swaying legs to ask for work. There was no mistaking; Ah Min was a <em>sinkeh</em> fresh off the boat, a newly arrived Chinese labourer. As he stood there in his black farmer’s jacket and pants, and farmer’s hat, and with the metal trunks and bags beside him, he attracted many probing stares.

The two Hakka migrants end up working in a gold-mining settlement called Mau San and find themselves embroiled in the 1857 Chinese miners’ rebellion.

A century later Therese’s grandfather, then a young man, is also involved in a rebellion. He joins communist insurgents trying to overthrow the post-colonial government of Sarawak, which had just been incorporated into Malaysia. The life of an insurgent is accurately depicted, with the greatest enemies being sickness and hunger. In this passage Therese’s grandfather describes a malnourished baby in the jungle camp:

I took a look at little Lin Sun, and my heart hurt. Yes, it literally hurt as though I was having a heart attack. The bones in his tiny body were all protruding and looked as if they would break through his translucent skin. His eyes were dull, sunken, lifeless. I held out my arms and Bong placed his baby into them. He turned to hold Li again and comfort her. Lin Sun felt so light, his elongated frame could weigh no more than six pounds. I could not bear to look at his face. I closed my eyes and in my mind saw the little cherub smiling and cooing as he had done five months previously. And I broke down, trembling, raining tears on Lin Sun.

Although Ghost Cave is well written, for readers who prefer a leaner style, there might sometimes be too much explanation of character motivations and a surplus of background information. Personally, I enjoyed the rich details and found the novel informative. I hadn’t realised, for example, the extent of Chinese migration to the territory; despite many migrants returning to China or moving elsewhere, enough stayed and prospered that Sarawak’s ethnic Chinese now account for a quarter of the population.

The plotting in Ghost Cave is excellent, the story switching smoothly between the three main settings – the 1850s, the 1960s, and the present – and there are enough twists and suspense to keep readers turning the pages. At the end, the various strands running through the novel are tied up neatly in a way that does not feel contrived. Another admirable feature of the novel is the likeability of the characters. While there’s plenty of darkness, this comes mainly from tragedies brought on by simple misfortune and the currents of troubled times; almost all the characters are sympathetic, and this makes for an affirming human story of triumphant love and family.

Ghost Cave is not biographical, but the historical background is factual, based on extensive reading and four research trips to Sarawak. It also draws on Sze’s own family history. Her father’s hometown of Buso is near the novel’s main setting, the Hakka mining settlement of Mau San (now renamed Bau). On the eve of the Second World War, Sze’s father left Sarawak to study in Hong Kong and eventually settled there. Elsie Sze was born and grew up in Hong Kong, and moved to Canada when she was twenty-two. After working as a high school teacher and then a librarian, she retired in 2001 to devote herself to writing. Sze’s first novel, Hui Gui: A Chinese Story, was published in 2005, followed by The Heart of the Buddha in 2009 and Ghost Cave: A Novel of Sarawak in 2014.

Sze’s novels are a wonderful example of how writing fiction – unlike most other arts – rather than extract a penalty for a late start, rewards life experience.

To learn more about the author and her books, visit www.elsiesze.com

Ghost Cave is published by the Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society and is available through Amazon.