Joyce Bergvelt is the author of Lord of Formosa, a historical drama describing the fight for Taiwan in the seventeenth century between the Dutch and the pirate warlord and Ming loyalist Koxinga. Like Koxinga himself, who was born to a Japanese mother and a Chinese father, Bergvelt has lived in Japan, China, and Taiwan. She left her native Holland for Japan at the age of ten, her nomadic childhood later taking her to England and then to Taiwan, where she studied Chinese at National Taiwan Normal University. Bergvelt returned to England to embark on a degree in Chinese Studies at the University of Durham, which took her to Beijing for a year at Renmin University.

Photo: Joyce Bergvelt in Taroko Gorge, Taiwan (1988)

What was the inspiration for writing Lord of Formosa?

The answer to that goes back to 1983, when I arrived in Taiwan with my parents in my teens. It was then that I learnt that Taiwan had once been a Dutch colony. This intrigued me. I read about Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), but information on the Dutch, who they were and what they were doing on Taiwan was limited. When I had to decide on a subject for my academic dissertation for my Chinese Studies degree at Durham University (UK), I didn’t have to think very hard. My final dissertation had the title: ‘The Battle of Taiwan: Taiwan under the Occupation of the Dutch and their Expulsion by Koxinga.’ Not a very catchy title.

It was all factual, of course, but I wrote it in chapters, alternating between Koxinga’s story and that of the Dutch, leading up to the final climax of the siege. My history professor gave me a good assessment; he even told me that it read ‘like an exciting novel.’

That comment stayed with me. I, too, found the story pretty amazing. There was so much human drama behind it, on both the Dutch side as on Koxinga’s. Upon my return to the Netherlands, I found that hardly anyone knew that Taiwan had been occupied by the Dutch. It was something I wanted to set right, as I felt it was a tale worth telling. I vowed to write about it in novel form for a broader audience, as it had all the ingredients for a novel. It is set against the glory days of the VOC (Dutch East India Company), which coincided with the fall of the Ming dynasty, a very turbulent period in the history of China. It hosts a number of fascinating historical characters, many of whom had to deal with emotional conflicts. Add to that the intrigue, betrayal and courage displayed on both sides, the drama of wartime and you have a great mix. So, the dissertation I wrote actually formed the backbone for Lord of Formosa.

It did take me twenty years to finally get down to writing it. The actual book took me three and a half years to finish.

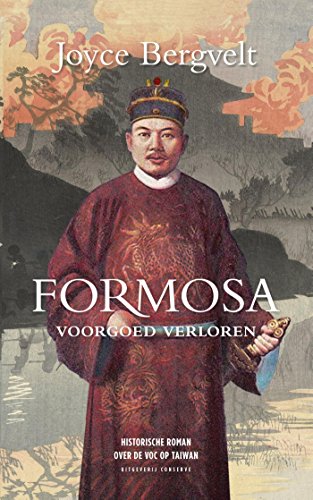

Lord of Formosa has had a long journey, with the English manuscript translated into Dutch and published in 2015 under the title Formosa voorgoed verloren (Formosa Lost Forever).

I originally wrote the book in English, completing the manuscript around 2010. Upon my return to Holland I found a Dutch literary agent who was very interested. He pitched the English manuscript to his counterparts and publishers in the U.S., but following the crisis, the book publishing industry took a serious hit, and no-one dared take on an unknown – and unpublished – Dutch author (at least this is what I like to tell myself).

My agent then advised me to translate the book into Dutch, which I did. By the time I had finished, the agent in question had shifted his focus onto translation rights for authors such as Dan Brown, Stephen King and Scandinavian thriller-writers, rather than spending too much time and energy on a first-time author such as myself. It was a commercial decision on his part that I can respect. Soon after, I found a publisher myself, Uitgeverij Conserve, which has two specialties: historical novels and books on the old Dutch colonies. It was a perfect fit.

When Camphor Press agreed to publish an English-language edition, the novel was improved upon and edited far more rigorously than the Dutch book was. Apart from the usual grammar and spelling edits, much more attention was given to geographical detail, Chinese names, romanisation, historical detail, even the use of local dialect. With the input of editors Michael Cannings and Mark Swofford, who specialize in books on the region, the novel has become so much better.

How was Formosa voorgoed verloren received in the Netherlands?

The book launch was hosted by Taiwan Representative Office in The Hague, which attracted some media coverage. The book itself was well received in Holland, both by literary reviewers and the public. It made the long-list for a literary debut award (Hebban) and was given three out of five stars by NRC Handelsblad (Holland’s leading paper). They even put the book cover on the front page of the cultural supplement! There have been many positive reviews, also among readers, with an average of 4.7 stars out of 5, which was heartening. It’s currently in its third print run.

Photo: Book launch of Dutch edition at the Hague with Taiwan Representative to the Netherlands Tom Chou (2015)

How well known is the Koxinga story there?

The story is hardly known at all in Holland. In Taiwan, the Dutch period marks the beginning of the island’s ‘official’ history, while the Dutch preferred to move on and forget the entire episode after they lost Formosa.

The older (80+) generation did learn about it at school, but often people don’t realize that Formosa and Taiwan are one and the same island. Modern Dutch history school books scarcely mention it, and when they do, it’s usually no more than a sentence or two.

Happily, that is gradually changing. There has been a renewed interest in the VOC in recent years, and due to the publication of a number of books (of course I’d like to think mine was one of them!) people are becoming more aware of the fact that ‘we’ once colonized Taiwan.

Lord of Formosa follows the parallel fortunes of Ming-dynasty warlord Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga) and the Dutch colony in Taiwan, with a focus on Governor Frederick Coyett. The climax, of course, is the Siege of Fort Zeelandia in 1661/62. In writing a story about Koxinga’s conquest of the Dutch colony, Coyett is the natural choice as a rival figure, and the fall of Fort Zeelandia is an obvious end point, but how did you decide on starting points for the story?

That wasn’t easy. As mentioned earlier, the academic dissertation formed the basis, but I wanted to tell the human side of the story through the eyes of those who lived through it. I felt the (brief) prologue was necessary to explain how it was possible that a foreign power could so easily claim an island the size of Formosa as its own. Originally, the first chapter that followed told of how the Dutch actually came to arrive on Formosa: the countless battles and skirmishes, the endless negotiations with the magistrates in Fujian, but I deleted the entire chapter. I felt it was tiresome and that it delayed the actual story I wanted to tell. Instead, I incorporated some of this information into the first couple of chapters. That brought the next chapter forward, with Koxinga as a young boy in Japan, just before he was taken from his mother to live with his family in China. That was an easy decision to make, as it is an emotionally charged time in his (and his mother’s) life. It wouldn’t have been interesting to write about his early childhood, as little is known of him during that time, and a young child’s world and perspective isn’t very interesting anyway in historical fiction. I then switched the focus to Formosa, where the Dutch had already been for some time.

Can you please explain what VOC means?

Good question, as the VOC insignia is prominently displayed on the cover. The VOC is the abbreviation for Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, known in English as the Dutch East India Company. The company was the result of a joint venture between two major trading houses in the Dutch Republic in 1602. It was a rather reluctant union, but the Dutch didn’t have any choice if they wanted to be able to compete with the rising naval power of the other trading nations at that time: the Portuguese, the Spanish and the English. The VOC was the world’s first multinational, in that it traded with many nations, had offices across Asia, and employed thousands of foreigners. It had its headquarters and governor-general (CEO) in Batavia, what is now Jakarta, with its Board of Directors (Heren Seventien) in the Dutch Republic. It was also the world’s first limited company. In the interest of commerce, the VOC was given sovereign powers, which meant that it could conquer enemy ships, wage war on others, and colonize land as it thought fit.

Can you tell us something about the cover illustration?

I love the cover illustration. It is composed of two well-known and much-loved images: one of the famous, beautiful map of Formosa by Johannes Vingboons (1640), and another of a 17th century engraving of Fort Zeelandia and surroundings, (artist unknown). These two were fused together, rather artfully, I find. The section of the map, where most of the story takes place, doubles as dark clouds gather over Formosa. Very appropriate!

What books would you recommend for readers looking to learn more about the history behind the novel?

When I wrote the dissertation back in 1987, I had to struggle through some old Dutch books (I was extremely lucky to find these at the Oriental Department’s own library at Durham University that existed at the time). At the back of the book, there’s an extensive list of the sources that I used back then, as well as more modern books. Leonard Blusse’s scholarly The Source Publications of the Daghregisters (Journals) of Zeelandia Castle at Formosa (1629-1662) was very valuable. Many later non-fiction books on this period drew heavily on this source.

From the more recent non-fiction books that have been written on the period, Tonio Andrade’s How Taiwan Became Chinese (Gutenberg Press) was a very good source. His later book Lost Colony (Princeton University Press) is excellent. Strangely, the Dutch translation of his book – which was well received in Holland – appeared in the same week that my own book was released here. I definitely recommend Lost Colony; it’s a good read and very comprehensive.

Jonathan Clement’s biography of Koxinga, Coxinga and the fall of the Ming dynasty, a biography on Koxinga, is also worth reading.

Did you make any changes to the known facts in the interest of a better story?

I didn’t make any changes to the story, but I did have to make a number of choices. I had to cut down on the number of battles – there were simply too many – and I had to limit the number of characters for fear of it becoming too long and incomprehensible. That meant ‘fusing’ a few minor characters and leaving some out. The trickiest part was deciding which sources to use when they conflicted. Generally speaking I would then choose the most likely and best documented scenario.

When writing non-fiction about historical figures, the gaps in the factual knowledge pose a challenge but give the novelist a certain freedom. What gaps exist in what we know about Koxinga and how did you handle them?

We know very little of Koxinga’s childhood and his years as a scholar, but we do know of his father’s growing trade imperium, and what was happening around him: a dynasty was about to come to an end, the country was about to be invaded and on the verge of war. I could have filled this gap on his personal life in with conjured-up detail, but instead I decided to make a few jumps in time to the moment when we do know more about him. This also gave me a chance to switch the story to that of the Dutch on Formosa, and back again. That’s the luxury of writing a novel: you can fill in the gaps where sources are lacking. For me, writing a historical novel means translating cold facts into visual scenes, by putting words in the characters’ mouths and putting thoughts in their minds, and all that set against a historical background. And then to weave it all together into a tapestry: the facts, the fiction, and all the colours in between. The historical facts serve as a beacon, a guide, but they can also feel like a straitjacket at times. Filling in the gaps is where I get to take liberties, and where I get to use my imagination. For me, that’s the fun part.

In how much detail did you map out the story before writing it?

In far too much detail. As it follows the story as lined up in my dissertation, I was quite regimental, making one timeline of historical events and one for the life events of the main characters, and finally merging those before I started writing. I was swamped with information, and I really had to lose a lot of it. I think I must have deleted about 130 pages before it found its way to the publisher. Gave me a couple of grey hairs!

In Lord of Formosa you give a largely sympathetic portrayal of Governor Coyett, which I believe works well in terms of narrative. Although history has been rather kind to him – in part because holding out for so long was a truly heroic achievement but also because his memoir was influential in shifting blame – his contemporaries gave him a mixed appraisal. Was showing Coyett in a favourable light a matter of your impression of the man or was it a conscious choice for the benefit of the novel?

Definitely the first. Of all the information I gathered about him, including his memoirs, I had to make a personality profile of what he was like. I did this by adding up all the facts and turning it into an equation: his life events, the decisions that he made, the things that he did, his achievements, how he reacted when put under pressure, his enemies, his family, his friends. By immersing myself into all of this the way I did for three and a half years, I became nearly obsessed with the man, and it felt as if I knew him. He was headstrong, even foolhardy, but I liked him. Coyett simply had a job to do, and he had to do it with the limited means that he was given. He warned the Council in Batavia countless times of the dangers that Koxinga posed. Not only did he have to deal with Koxinga and his army, but also with double-dealing trade intermediaries, popular uprisings, rebellious missionaries, a bitterly jealous predecessor and a vengeful Dutch admiral whom he had crossed. As the first in command on Formosa, he had to make swift decisions, often unable to wait for the green light from Batavia, which could take two to three months. For this he was criticized. His wasn’t an easy job. On top of all that he had his share of personal loss. So yes, I sympathized with him, and I admired him.

Do you have any favourites among the minor characters? Personally, I’m quite fond of the Dutch doctor Christian Beyer.

He was quite a character, wasn’t he? He was sent – with some reluctance – to treat Koxinga for his illness on Amoy, where he stayed for nine weeks. In a sense he was quite an important character, as he was the only Dutchman who really got to know Koxinga on a personal basis. There isn’t much known about what type of man Beyer was, so his personality as portrayed in the book is how I imagined him to be. I rather liked him too!

I applaud your decision to give the translator He Ting-Bin an important role in the novel. Not only does he provide you with the spice of treachery and intrigue, but as a character moving between the worlds of the Dutch and the Chinese, he helps weave the two streams of the novel together. And, he was in actuality one of the most important figures in the real historical drama. Without his dishonest sales pitch to Koxinga on the riches awaiting and an assurance of easy victory, the Dutch colony might not have come under attack.

Thank you. He Ting-bin was an interpreter/translator for the VOC and a wealthy, well-connected merchant whom the VOC had appointed trade intermediary for their trade deals with the Zhengs (Koxinga’s family). Not a very trustworthy character, but the Dutch didn’t have any alternative. Yes, I saw at an early stage that he should play a key role, as he was one of the very few men who had good contacts with both the Dutch authorities on Formosa as well as with the Zhengs. His story intrigued me. With his double-dealing, his greed and deviousness he wasn’t exactly a likeable character, but I do have grudging admiration for him.

What do you like to read in your free time?

Not surprisingly, I love historical fiction, especially if it’s based on fact. Due to the fact that I grew up in Asia, I developed a penchant for books on the region. In the seventies and eighties that meant authors like James Clavell, James Michener, Han Suyin, Robert Elegant, and more recently, Amy Tan, Anchee Min, Lisa See and Amitav Ghosh. I’ve also lived in the Middle East and Australia, and my parents lived in Hong Kong and India for a number of years, so I’ve been exposed to ‘world literature’ for as long as I can remember. And that’s a great privilege. Naturally I deviate from historical fiction from time to time – there are so many good books to choose from, non-fiction among them. But I do find I’ve become a far more critical reader since I started writing, so I am selective. I always look for stories with a multicultural theme, about characters who find themselves in a world that is not their own and who have to struggle to rebuild their lives in a country other than that of their births.

Although I do read Dutch books from time to time, I mostly read in English. There are exceptions, but I often find (modern) Dutch literature a bit claustrophobic. Must be me. ?

Lord of Formosa is published (April, 2018) by Camphor Press. It is also available from other retailers such as Amazon.com.