The Pearl River Delta is home to Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Macau, Shenzhen, and cities of millions – such as gritty workshops to the world Dongguan and Zhongshan – that you’ve never heard of. Despite being the powerhouse of the country’s decades-long economic boom, China’s southern cities have been largely ignored by English-language novelists for the more glamorous settings of Shanghai and Beijing. When stories are set in the south, they are usually period pieces taking advantage of the region’s rich historical backdrops of war, revolution, and the treaty port clash of cultures. It was a welcome change to come across a novel set in modern-day Guangdong.

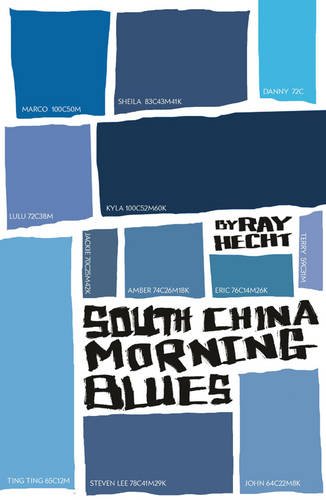

South China Morning Blues is divided into three sections, each named after a city in the region. The multiple storylines begin in Shenzhen, move to Guangzhou, and end on Lamma Island in Hong Kong. The novel provides a kaleidoscopic view of urban China as seen through the eyes of a dozen mostly twenty-something Chinese and foreign characters. There’s Marco, a macho American businessman looking to get laid at every opportunity; Danny, an English teacher finding his feet; intellectual stoner Eric; artist Ting Ting; American-Chinese journalist Terry; and… I’ll stop there. Twelve is too many to run through, which raises the question of whether that number of characters makes for an overcrowded cast.

Although there’s no consensus on the maximum number of main characters a novel should contain, it’s generally thought that eight or nine is the upper limit for a medium-length work. Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, for example — which, with its multiple narrator structure, was one of Hecht’s inspirations — has perhaps seven main characters. When I opened SCMB, and realized that Hecht had chosen twelve because he wanted one character for each animal sign of the Chinese zodiac, the approach seemed like a recipe for disaster.

Surprisingly the big cast works. Credit goes to the author for how he does this by adding a couple of characters at a time, building up layers, and coming back to earlier people as some of storylines are threaded together. The effect is an unusual but engrossing reading experience, an immersive feel of varying waves of engagement. The number and range of characters, subplots, and places gives the novel an epic flavour; it’s a big canvas which contrasts with the mundane considerations of daily life that the characters describe.

South China Morning Blues is written in a stream-of-consciousness, first-person narration. Unavoidably, this is sometimes inane and slow moving; but it’s also often funny and, above all, honest. The novel is painfully true to life: how we actually were when young and finding our way, rather than how we would like to remember ourselves. I laughed aloud in numerous places, perhaps most often for Danny, the non-descript English teacher and laowai newbie who is soon playing the veteran. In one such scene, a fellow English teacher – young, fresh off the boat, and completely clueless – asks Danny how long he has been in China.

“Well,” I say. “I’ve been in Shenzhen for a year now, but in China almost two years. Before here I lived in a town you’ve never heard of up north.”

“Wow,” he says, easily impressed. I feel cool, sophisticated.

One of the pleasures of SCMB is seeing how characters grow up (or don’t) over the two-year period of the novel. Eager to know how things worked out for them, I raced through the book in three days, pleased with the ending and yet sad the story had come to a close.

SCMB contains a lot of drinking, drug-taking, and sex, but not unrealistically so. Alcohol and drugs are a social lubricant and stress-relief for people in a new place. Likewise, business entertaining in China involves heavy drinking and frequently a side-dish of whoring, so it’s not unnatural that when Marco, the self-styled Casanova, is on a business trip to Dongguan, he should partake of the city’s infamous delights. Marco takes two hookers back to his hotel and is working his magic while the women watch television:

In front of me, I have two bare asses. They cost me only a grand each. That’s in RMB.

Enthusiastically, I slap the one on the left and pound away against the other one. She insisted that I wear a rubber. That part never gets lost in translation. This experience would have felt better without, but whatever….

I wish that I could persuade these girls to perform some lesbian shit. I push their heads together. They kind of kiss for a second, but then smirk and turn away. Don’t these bitches watch porn, or what?

My cock feels ready to explode out from under me, almost like I should call in a bomb threat to the hotel or something.

At times SCMB can be a bit depressing in portraying the shallowness of many Chinese–foreign interactions, but once again it rings true. In fact, I’ve met people like all twelve of the story’s characters. Much of the realism comes from author Ray Hecht writing about what he has himself experienced or seen, having lived in the novel’s two main locations, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Hecht, who was born in Israel but grew up in the American Midwest, arrived in China in 2008 at the age of twenty-six. He works in Shenzhen as a writer and teacher, and has written two previous novels: The Ghost of Lotus Mountain Brothel and Loser Parade.

South China Morning Blues deserves to sell well. It’s easy to see the novel becoming a big hit among the expat population in China, but it should also appeal to general readers. Hecht’s Pearl River Delta tapestry is at heart a racy drama exploring universal themes, so no knowledge of China is required to enjoy it.

* * *

South China Morning Blues is published by Blacksmith Books. It’s available from the publisher’s website, Amazon, and bookstores in Hong Kong.

Author Ray Hecht has a website chronicling aspects of his writing and life in Shenzhen.