Are foreign English teachers in Asia losers? The usual caveats aside about the unfairness of painting whole swathes of a population with such broad strokes, yes, there are enough deadbeats to justify the stereotype.

I recall my first day at an upmarket exam prep school in Taipei, the director explaining as I walked to class that the teacher I was replacing had been fired a few days earlier after emailing all his students a photo of his yang implement. At least that was nudity at a distance and pixelated, unlike the teacher who had a meltdown mid-lecture, stormed out of the classroom and minutes later was in a nearby coffee shop, standing stark naked atop a table, ranting wildly and quoting Shakespeare (I know there will be two reactions to this episode; normal people will think it outrageous, but many English teachers will be “wowing” in admiration that the guy could quote Shakespeare and wondering if it’s really fair to call him a loser). For a less erudite example, there was the teacher, who, vanishing with a seventeen-year-old female student, was next sighted in the southern resort of Kending leading the poor girl around the beach on a leash, both stoned immaculate. There was a happy ending, of sorts; when the teacher finally resurfaced at work, some gangster muscle burst into his class and administered a much deserved smack-down in front of the students. I could go on for hours.

Thankfully, things have been much tamer in Taiwan over the last decade. The English-language industry has matured and become more regulated, standards have risen, and greater competition for fewer jobs means schools can be choosy. For a good while now, the biggest Asia-bound losers have been heading to China.

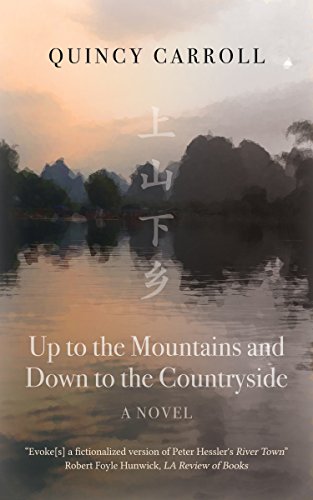

Daniel, the main character of Quincy Carroll’s excellent debut novel, Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside, has a similarly bleak view of his fellow laowai:

The place was like a playground for foreigners. For the most part, you were respected, and it was never hard to find work, and there were countless oddballs around every corner, exploiting their status for all it was worth. Thomas was not even one of the more outrageous characters he had met. The cities were full of them: blubbery old white men with no money but all of the confidence in the world.

As well as being the prime destination for the personality-challenged, skills-free, semi-literate teacher with a fake degree (and sometimes a fake accent), China also attracts earnest graduates looking for meaningful cultural exchange. These two extremes often collide in small inland towns, thrown together for opposite reasons; the young idealists are seeking an authentic experience away from the modern “Westernized” coastal cities; the bums are looking for jobs with lower entry requirements in areas where most foreigners don’t want to go.

Such is the set-up in Carroll’s novel. The heart of the story is the strained relationship between two American English teachers during an academic year in the small town of Ningyuan. There’s likeable Daniel, a few years out of university, and the misanthropic Thomas Gulliard. The novel opens with Thomas waiting at a station for the next bus to Ningyuan.

For two years now, he had been living in their country, in a crowded metropolis where you rarely glimpsed the sun, forgotten by his people and his people lost to him. Yet despite this estrangement from his family and his friends, he felt no greater bond of kinship among the Chinese with whom he lived. He was a man of more than sixty, gaunt and disheveled, with sparse gray whiskers surrounding his mouth and a sharp, protruding jaw that called attention to his chin.

It’s clear early on that Thomas’ unattractive appearance comes with an even more repellent personality. Befriended at the station by precocious high school student Bella, he wolfs down her food with little gratitude and ends up cadging money for the bus ticket (he has spent some of his last bills on beer and cigarettes).

They sat together on the floor of the station, eating noodles from paper bowls. Bella told him of the town and its people and the places she had been, while Guillard listened impatiently, slurping at his food. He had already made his way through two oranges and a moon cake and an egg that had been steeped in tea, and the rinds from the fruit lay strewn about his person, like so many fallen leaves. As though he himself were deciduous in nature. Fragments of the eggshell littered his clothes, and with a contorted hand, he set down the noodles and wiped at his chin, then began to pick them individually from the surface of his chest. In time, he was able to tune out Bella, carping aloud in his head.

Already teaching at the school in Ningyuan is Daniel, handsome but rather freakish on first appearance with his tattooed arms, pierced ears, and long, red hair. He’s friendly, fluent in Chinese, popular with the students, teachers and the townspeople, and perhaps most annoyingly, one of those guitar-playing foreigners that women find so irresistible. Although Ningyuan is considered a dull backwater, for Daniel it’s an idyllic place and he enjoys exploring the countryside on his motorbike.

On the weekends, Daniel would go riding, up through the hillsides surrounding town, down through the paddies and quarries and aquaculture ponds that dotted the land. The roads were narrow but often untraveled, and the hamlets lay sleepy in the afternoons, no signs of occupancy but for the litter—occasionally, a dog. He followed the pavement for miles on end. The locals who saw him always seemed unsettled, for he came without warning, then he was gone—the young, tattooed foreigner with ears like the Buddha, hair the color of fire.

The two Americans work together and live together, neighbors at the on-campus accommodation, and both are hounded by Bella. She’s a student at their school, friendly but very tiring, one of those overzealous learners who ambushes you with never-ending questions.

Daniel soon discovers his compatriot to be “arrogant, lewd, and racist,” above all an embarrassment. Thomas in turn is irritated by what he sees as Daniel’s smug, naive idealism. Thomas tells Bella:

He thinks that just because he’s in China, he’s doing something special with his life.… After all is said and done, he’s here for the exact same reasons as the rest of us: easy living, zero responsibility, and a chance to make himself into whatever he wants.

I wish the author had made Thomas a more sympathetic character. Although Thomas is virtually without any redeeming characteristics, he’s not an especially bad English teacher by China standards; he’s a native English speaker, isn’t dealing drugs, stealing from co-workers, hiding out from a murder rap, or staging fake kidnappings of his daughter to extort money from his in-laws. The problem with him being such a miserable bastard is that we take Daniel’s side and dismiss Thomas’ criticisms too easily. Thomas is justified in calling Daniel naïve, not least because the young man is working as a volunteer, whereas the old cynic is getting paid a proper salary. This obviously bristles. As Thomas settles into living in Ningyuan, he has: “money to burn, and, compared to the volunteers, his pay was excellent. Outrageous, in fact. He watched them scrimp and save their earnings—eating at street stalls, cooking at home—while he dined at Old Tree, a western-style restaurant….”

I’m afraid I agree with Sinosplice blogger and former ChinesePod host, John Pasden, when he writes:

I can’t help but see most volunteers in China as suckers.… Too often, the teachers are new to China and very naive. They realize their pay is very low, but they explain it with, “China is very poor.” After living in China for about a year, they often learn that the local director for their program drives a BMW, that other English teachers make about three times what they do for the same work, and that their students are no more disadvantaged than most kids in China.

Author Quincy Carroll was himself a volunteer teacher in Ningyuan for two years. Though Ningyuan is described as a small town, in China this means it has the population, chaos, and noise of a city. Don’t imagine some bucolic village. In the novel we learn that the school at which the Americans teach has a total of more than seven thousand students. Ningyuan is in south-central China, Hunan Province, which is slightly smaller in area than the United Kingdom and with a similar population. It’s not especially well known, but you may have heard of it in relation to Mao Zedong (he was born there) or the film Avatar (the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, with its stunning karst landscape of sandstone pillars rising out of sub-tropical rainforest, is often cited as an inspiration for the beautiful Pandora setting of James Cameron’s 2009 movie).

Carroll is an American from Massachusetts who went to China after graduating from Yale in 2007. Following his two-year stint in Ningyuan, he studied fiction writing back in the States. He then returned to Hunan, this time for a year in the provincial capital of Changsha, working as a copywriter for a consumer electronics company while finishing his novel. He currently lives in California, where he teaches Mandarin at a charter school.

Given that the novel is a realistic look at the lives of English teachers in a backwater town, there’s inevitably some dullness. The story is carried by Carroll’s precise and evocative prose, the flowing rhythm of his sentences.

Carroll, emulating his favourite writer, Cormac McCarthy, does not use quotation marks. Although this device is a bit unsettling at first, the dialogue is written in such a way that we know who is speaking, so I soon got used to it. This omission, however, blurs the lines between protagonists and narrator, and with the third-person narration so in accord with Daniel’s voice I’m not sure it works. (Added detail for language geeks: Carroll also copies McCarthy’s punctuation style in not including a single semicolon.)

A minor word of warning about the writing: Don’t be misled by the opening paragraphs. Like a painter overworking a canvas, Carroll seems to have gone back to the first chapter again and again adding unneeded lexical complexity. The novel begins with:

He stood in the waiting hall of the station, searching the crowd for a seat, the Chinese squatting among their baggage and eyeing him like children through the half-muted light of the clerestory. The air was smoke-filled and dusty and close and very hot, and as the sun set, the shadows from the muntins tracked its course overhead.

This is soon followed by: “a girl sitting with her legs crossed atop a gingham-print bag. A rosacea birthmark spoiling her chin. She wore a white cotton shirt with the placket unbuttoned and the image of an Osmanthus tree sewn across the heart.”

What’s a “clerestory”? A “muntin”? A “placket”? I had to check a dictionary for those. Coming across the occasional new word is pleasingly educational, but in such rapid succession you start feeling stupid. This early onslaught is not representative of the smoother prose in the rest of the book.

(Note: the problems noted above have been addressed by the new publisher in the second edition of the book.)

The plot of Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is a simple one. Tensions between the two main characters build gradually to a series of showdowns and a climax. There’s a nice twist at the end, and then a suitably inconclusive ending. Added sub-plots would have created more drama, but taken away from the realism, and distracted from the issues the novel raises.

Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is a good choice for anyone who has spent time in China or who has worked overseas. It’s a thought-provoking, beautifully written rumination on the expatriate experience. Carroll is a talented young writer and I hope he keeps writing about China.

The novel was originally published by Inkshares. The second edition is published by Camphor Press and is also available from Amazon.com and other retailers.

Click to read a Bookish Asia Author Interview with Quincy Carroll.