Like many long-term expats in Taiwan, American Scott Ezell’s first encounter with the country was rather incidental. He came in 1992, on a friend’s recommendation, to study Chinese, an interest that sprang from his love of the Tang dynasty poets, polymath bohemians like Li Bai who celebrated and lived contemplative yet enjoyable lives of nature, wine, and the rejection of material ambition. Ezell says he “arrived in Taiwan with visions of Taoist recluses drinking wine in bamboo groves and Zen monks cutting cats in half to prove that the world is an illusion.” Of course, what he found was something rather different – the noisy, materialistic frenzy of a Little Dragon in a headlong rush of development.

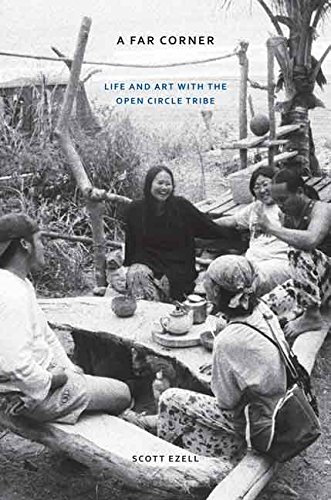

In 2002, after a decade in Taipei studying and working as a translator and musician, he left the big city and moved to the coastal village of Dulan in a rural coastal area in southeast Taiwan. He would soon find his own Taoist-like band of bohemians, a group of aboriginal artists, predominantly of the Ami tribe, who informally went by the name of the Open Circle Tribe.

He was welcomed from the beginning. Early on, he found himself on the beach: “I did not realize it at the time, but sitting around a fire, passing mijiu, songs, and a guitar around a circle of friends would essentially comprise my social life for the coming two and a half years I lived in Dulan.”

His aboriginal artist friends were musicians and wood carvers (typically of driftwood and rather disappointingly using chainsaws). Ezell’s main art form was musical composition, his biggest project being a 2003 album Ocean Hieroglyphics, recorded in a remote house away from chainsaws – where he set up an old school analog recording studio.

Scott Ezell, as well as being a musician and artist, is a poet. I’m biased against modern poetry – it’s a generally lazy, self-indulgent form – but I have to admit that Ezell’s poetic leanings enrich his prose. He can certainly write and A Far Corner (2015), which chronicles his time in Dulan, is full of memorable phrasing. And to get such a lyrical account – both in style and subject matter – from a university press is a welcome surprise.

Here’s an example of Ezell’s magnificent descriptive powers:

July, the gut and groin of summer, the days sticky and thick with heat. Ducking out of the sun became a movement both primary and unconscious, an instinct like dodging a blow or swatting at the whine of a mosquito by your ear. The mountains that were sharp green in spring became drab and muted, as if their color was a blade hammered dull by heat. The ocean sank into a brooding blue, its currents and movements retreated beneath the surface, leaving a skin like old paint to absorb the crash and roar of the sun. The air hazed and thickened, the smell of decomposition climbing through like vines, rising up from the soil, from wilting leaves. Flowers shriveled, leaving seed pods that rattled as I moved through the brush up on the mountain. The sky yawned, blank and empty, a bored god, butane blue….

His descriptions of aboriginal music and singers are moving, too, though can tend, for my tastes, to the overly romanticized:

The Chief stood up from his chair. His voice evoked the hills and ravines of Dulan, the undulating bluffs along the coast, the texture of the sea breaking blue-green over stones. The Amis songs had a rhythm and pulse that belonged to this place, passed down breath by breath through generations.

I think Ezell is at his best when he’s describing mundane things such as a mom and pop supermarket.

His store was a yowling chaos, with ten times too many things crammed on dusty shelves with no apparent organization, a mayhem of mercantile accumulation. … On a butcher’s block by the cash register, slabs of pork lay for sale beneath a mesh dome, the wood scarred and concave from decades of chopping meat. A mechanical fly whisk turned above, a bit of plastic twine tied to a length of rotating coat hanger.

Scott Ezell’s time in Dulan reached a climax at a big concert at an old sugar factory which had been turned into an arts and culture center. Undercover cops claimed Ezell had played music in public, which was a violation of his visa. Although Ezell’s residence visa was sponsored by a record company, it did not specifically include a right to perform music in public. Now, if this applied to only paid musical performances, that would be one thing – but unpaid performances were also technically illegal according to the interpretation. Of course, only someone with malignant intentions would try to enforce it; Ezell says this was the case, a local police officer with a grudge against foreigners.

Ezell’s residence permit was cancelled and he was given two weeks to leave the country. A Taiwanese lawyer friend, Roger Wang, fought his case, and the musical community and the English-language press made a lot of noise. (As an aside, Ezell says that the case never made it into the Chinese-language newspapers.) Ezell managed to get a stay on the cancellation of his residence visa until the legal case had been settled. Although he was likely to win it, he chose not to stay and fight. Living under a cloud of deportation, and being barred from playing music at the sugar factory or elsewhere in public would remove much of his fun. In addition, Ezell feared the police might hassle his friends to get at him, so he decided to leave Taiwan.

Taipei Times book reviewer Bradley Winterton wrote a rave review of A Far Corner, praising Ezell’s “ability to evoke Aboriginal life even within its contemporary, often degraded context. He sees the poetry behind the plastic, as well as the eternal behind the transitory. The poet within him co-exists triumphantly with the cool observer.” Winterton called the book “magnificent” and predicted that it would “become a classic English-language book about Taiwan.” Alas, the book, like most, has largely slipped under the radar, but it does indeed deserve to be much better known than it is.

A Far Corner: Life and Art with the Open Circle Tribe is published by the University of Nebraska Press. It is also available on Amazon.com and other retailers.

Scott Ezell writes at scottezell.org