I first came across Graeme Sheppard’s book last year, only it was an earlier version: Life & Death in Old Peking: The Murder of Pamela Werner. As one of the chaps behind independent publisher Camphor Press, I’m always on the outlook for new titles. Every so often I trawl through the self-published books on Amazon with the hope of finding a rare gem worth acquiring. When I saw Life & Death in Old Peking, the book piqued my interest, but I didn’t follow up and read it. I guessed it was substandard (why hadn’t the author been able to find a publisher for such a juicy topic?) and the author was likely trying to ride on the coattails of the phenomenal success of Paul French’s Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China. And, anyway, I wouldn’t want to put out a book in competition with French’s; I’m a fan of his work and he’s given a lot of support to Camphor Press, including writing an introduction for our abridged Carl Crow traveler’s handbook, China 1921: The Travel Guide.

I did, however, keep an eye open for mentions of Sheppard’s book on French’s excellent China Rhyming blog, where he periodically makes posts related to the Werner case (looking there just now I see a plug for an upcoming Midnight in Peking walking tour). There was deafening silence on the blog, which was odd – French is not a close-mouthed man by any means. After Sheppard’s book was picked up by China veteran Graham Earnshaw and published by his Earnshaw Books, I finally decided to read it.

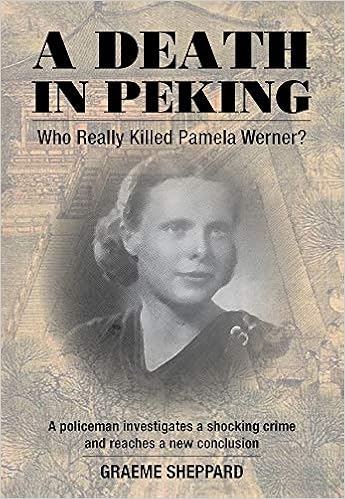

What a revelation! A Death in Peking: Who Really Killed Pamela Werner? is the most memorable book I’ve read this year. It reexamines the unsolved January 1937 murder of a 19-year-old British girl, whose mutilated body was found found lying in a gully along Peking’s old Tartar Wall.Her face had been so badly slashed that identification proved difficult; more disturbingly, her heart was missing – it had been cut out of her chest. The girl was Pamela Werner, the adopted daughter of a retired British consul. She had last been seen at a skating rink in the nearby Legation Quarter and had been expected to cycle the short distance to her home in a hutong neighborhood outside the Legation Quarter.

Pamela’s brutal murder was a crime that shocked the expatriate community in China and briefly made international headlines, an unsolved crime which was pushed aside by the Sino-Japanese War and languished in obscurity until the publication of Paul French’s bestselling Midnight in Peking in 2011.

French’s book is a gripping exploration of a murder and also the city of Peking. Although Peking’s importance had been sidelined by the commercial growth of treaty ports such as Shanghai and Tianjin and by the Nationalist government moving the capital to Nanjing in the south of the country, this meant Peking’s ancient imperial splendor was better preserved. It was a magical place but one on borrowed time. In 1937, as the police searched for a killer, the city awaited conquest by Japanese forces camped on the outskirts.

Midnight in Peking has been praised for its engrossing narrative and for lifting the veil on expatriate life in 1930s China. Every second Westerner it seems is hiding a secret life. French has trouble resisting narrative flourishes, and – knowing the period like few writers do – has an embarrassment of riches at his disposal, making for a crowded canvas of characters. He’s fascinated by the foreign criminals then resident in Peking – especially in an area of brothels, cabarets, and drug dens known as the Badlands – and keen to work this into the narrative (he would go on to write a spin-off book The Badlands further exploring this area and its criminals).

The array of flawed foreigners profiled in this true crime story was a good match for modern sensibilities. French’s line-up of main murder suspects and the final trio he points to are Westerners. Unmasking the supposedly respectable foreign citizens of Peking appeals to twenty-first-century prejudices; no harm in the privileged, pompous, and arrogant European elite being shown in a poor light. We, the virtuous reader can enjoy the period detail safe in the knowledge we would have been one of the few good foreigners.

You can see this attitude in a review for the book in the Guardian newspaper by English historian Rana Mitter. He wrote:

In a welcome turn away from orientalist cliché, the book makes the westerners in Peking seem like an assortment of oddballs, standing out amid a crowd of Chinese who are getting on with their lives as best they can.

Well, all this coloring is fine, for a novel, or in a non-fiction work to a degree, but a murder investigation is a serious matter. Accusations of wrongdoing should be sober and based on solid information. However, this is not the case. The core problem is that French’s account relies too heavily on letters and reports written by Pamela’s father, E.T.C. (Edward) Werner. When the authorities closed the case, the father continued on his own, hiring detectives and offering rewards, writing continually to the authorities with claims he’d found the killers and unearthed new revelations. French stumbled across an uncatalogued file full of papers from Werner and came to agree with his conclusion as to the killers. This misdirection is understandable – discovering such a treasure trove of documents, you’d be predisposed to believing their veracity, and to feel sympathy for the father, who suffered the double tragedy of his wife dying when Pamela was five years old and then his daughter’s murder; and you couldn’t help but feel admiration at the old man’s perseverance and want a satisfying resolution to the case. Indeed, the very last line of Midnight in Peking is French’s statement of mission behind the book, his desire “that Pamela Werner not be forgotten, and that some sort of justice, however belated, be awarded her.”

Graeme Sheppard, a retired policeman from England, first heard of the Pamela Werner murder in Midnight in Peking. (Incidentally, he has a personal connection to the case: Nicholas Fitzmaurice, British consul in Peking at the time, was his wife’s grandfather). Sheppard was not convinced. “As an experienced police officer, I could not conceive how the police of the day had failed to identify so many of the leads the old man

Sheppard thought the book “unfair and inaccurate in its analysis and incorrect in its conclusions” that Pamela had been murdered by a trio of Western residents who were part of a sex ring. Sheppard decided to investigate the case himself (what audacity and determination!). It was an intensive three-year project that saw him uncover exciting new material related to the case.

Early on, Sheppard found French’s conclusions were based largely on Edward Werner’s letters, which was problematic.

it quickly became clear that the Werner reports were in no way objective and were written by a man possessing a strange mind. Crucially, nowhere did they contain any primary or admissible evidence. Without corroboration of any kind, they could not be taken seriously. For the large part, they were little more than rants. Unfortunately this was not made clear in Midnight in Peking. In presenting and supporting Werner’s case and conclusion, the book failed to mention his many contradictions, changes of mind, improbable scenarios and outlandish allegations.

Among the allegations was that Colonel Han, the Chinese Head of Police, who was in charge of the investigation, was in league with the murderers.

Investigation of other sources referenced in Midnight in Peking uncovered mistakes and problems; misattribution of quotes, quotes from unreliable sources (though not presented as such), invented dialogues and not just in the form of joining dots to add color, but dialogues for meetings that never took place. For example:

Nudism, naked dances, parties at his flat: these were all accusations raised only by Werner in his letters. In Midnight in Peking, they take the form of a police interview.

Important factual mistakes include a U.S. government file pertinent to French’s chief suspect, an American dentist called Wentworth Prentice. French says the file indicated there was concern about the safety of his youngest daughter, Constance, and that wife and daughter had fled China fearing the husband. As Sheppard says, “All damning stuff for Wentworth Prentice, but entirely wrong.” The file in fact referred to another woman surnamed Prentice, captured by bandits, a Christian missionary unrelated to the dentist and his family. Another faulty claim made against the dentist is that Pamela had a dental examination with him a month before her murder, whereas it was actually in 1930.

A Death in Peking is thorough, the author carefully going through the investigation and all the suspects, and with surprisingly little reference to Midnight in Peking until the end. It lacks some of the exoticism and cinematic moments of that book, and, at first, has less narrative punch, but chapter by chapter as you read it, the layers of detail and relentless levelheadedness have a devastating cumulative effect. This is death by a thousand cuts, with a short, brutal dispatch at the end when Sheppard takes Midnight in Peking to task and convincingly gives his verdict on the various suspects and names the most likely killer.

A Death in Peking: Who Really Killed Pamela Werner? is published by Earnshaw Books, and is also available from Amazon.com and various other retailers.