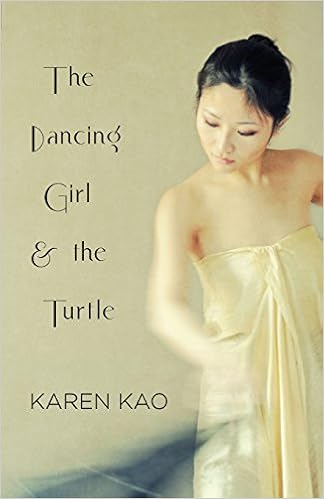

Karen Kao’s debut novel The Dancing Girl & the Turtle is an ambitious, striking addition to the novels showing the sleazy side of 1930s Shanghai.

Impatient to get to the magical city of Shanghai, recently orphaned 18-year-old Anyi Song disregards instructions to wait for an escort, setting off from Soochow by herself. “Soon, my Uncle and Auntie will find me on their doorstep and how surprised they’ll be! They’ll praise me for having found my way all alone from Soochow to Shanghai. They’ll welcome me into their home and my new life will begin.”

In one ot the most powerful opening scenes I’ve read, Anyi is brutally raped by a band of soldiers and left for dead. Taken to her aunt and uncle in Shanghai, she is nursed back to health while they set about finding a suitable husband. Anyi, however, is physically and mentally damaged, unable to escape from the trauma of the rape, a lost soul on a downward trajectory of hallucinations, self-loathing and self-harm. There are those who try to help her – an aunt and uncle, her cousin Cho, and her brother Kang, who comes back from the United States to see her – but it seems she might be beyond help.

Cho is the “turtle” (slang for a free-rider) of the title, a gambler, playboy, and opium user, who, despite being Anyi’s cousin, falls in love with her. Among the more bizarre characters of the novel is “Auntie” Wen (no relation), a blind masseuse who exploits Anyi’s budding masochism and ends up acting as her pimp. Anyi turns down the marriage her aunt and uncle have arranged, moves into her own apartment, and supports herself by dancing and prostitution, specializing in serving sadists.

Brutal yet not gratuitous, the novel doesn’t shy away from showing the horrors of sexual violence, but does so indirectly – the camera pans away for the worst of it.

I like this place, the Cathay Hotel. The walls are thick and the curtains heavy. No sound can escape. The customers who have no time for a hotel room take me in rickshaws or the alleys of the old walled city where my cries mingle with the agony of a thousand others.

This customer tonight, I’ve seen him before. He comes from Shandong and trades in wine. He opens his suitcase and takes out a whip.

‘Not the face or arms,’ I remind him. ‘The rest is all yours.’

Rather than describe the violence, the next line has Anyi returning home, being helped into a chair by Auntie Wen and a servant.

Anyi is a classic Chinese beauty and among her admirers is Tanizaki, an unhinged Japanese attaché. When Anyi first meets Tanizaki, she tells him she doesn’t want anything to do with Japanese, then fighting the Chinese in the city.

‘I don’t service Eastern devils,’ I say to him.

The man stiffens. ‘Auntie Wen warned me you’d say that. I’m willing to pay double.’

‘No.’

For one electric moment, we stare at each other. Then the man laughs, long and hard.

‘I like you,’ he says. ‘You have spirit. Very well, I’ll leave you in peace though I suspect we’ll meet again.’

Indeed, they do, and Tanizaki becomes obsessed with Anyi, and will soon hold her and Cho’s fate in his hands. While a memorable arch-villian, Tanizaki might have benefitted by having more nuance. He’s a sadist without redeeming attributes.

He’ll use whatever is within reach: an ashtray, a burning candle, his own belt. But what he likes best is to beat me with his own hands. I goad him on, each time a little farther. The bloodlust glitters in his eyes. His breath grows ragged as he chokes all the air out of my body. I arch my back hoping that he will pull the knife that’s strapped to his shin and slit me open from neck to navel.

Intense without being exploitative, you read such passages in the novel without feeling voyeuristic guilt. The Dancing Girl and the Turtle is an immensely sad story of how the trauma of rape remains and how internalizing shame poisons the victim. The novel is not all darkness though. There are uplifting elements here and there and the ending brings an exciting, surprising, and satisfying close to the story.

The writing itself is unsentimental, visual, and lean. However, my personal preference is for a less minimalist style. The story is written in the present tense, a modern trend of which I’m not a fan, and told in short episodes, switching between characters every few pages or so. To further complicate matters some of the narrative is in the first person, and at other times the third person.

Although those authorial choices meant the novel was not entirely my cup of tea, it is certainly well crafted and engaging. Author Karen Kao says it took her five years to write and it’s easy to see the labor and love she put into it.

The Dancing Girl & the Turtle is published by Linen Press, which describes itself as “a small, independent publisher run by women, for women,” and “the only indie women’s press in the United Kingdom.”

The novel can also be purchased at Amazon.com and various other retailers.

Karen Kao was born in United States to Chinese immigrants who moved there in the 1950s. She lives in the Netherlands. To learn more about Karen Kao and to read more of her writing, you can visit her website.