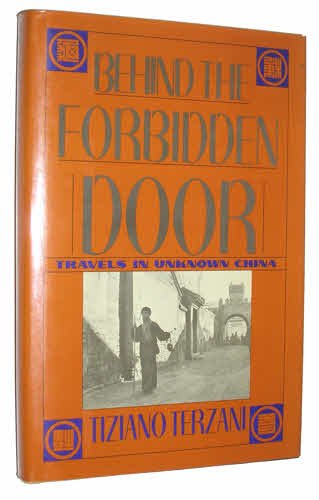

Tiziano Terzani was an Italian writer, journalist and adventurer, who spent decades living all across Asia. He was well known in Italy for his deep knowledge of Asian languages and cultures, and for his fascinating travel books. His book on his years in China, Behind the Forbidden Door: Travels in Unknown China (Henry Holt: 1986), must be one of the most piercing accounts written by an outsider about life in the Middle Kingdom following the death of Mao Zedong. As an Italian, the author also offers a slightly different perspective than the Anglo-Saxon one provided by the majority of famous authors who have written about living in China as a foreigner.

Born in Florence in 1937 to a family of modest means, Terzani led an extraordinary life, egged on by his curiosity and sense of adventure. After becoming a journalist, Terzani moved to South-east Asia in the early seventies to work as a correspondent for the German magazine Die Spiegel. He was present during the fall of Saigon and wrote a book about it. However, his real goal had always been to live in China. Terzani was fluent in Chinese, which he had learnt in Stanford in the late sixties, and had always felt an affinity for the country. Like many young people of his generation, he had been fascinated by the romanticized descriptions of Chairman Mao’s attempts to build a New China free of capitalism, imperialism and exploitation. Throughout the seventies he searched for a way to live in China, offering himself to the Chinese authorities as a language teacher and even as a chef, but never receiving an answer.

After the death of Mao in 1976 and China’s subsequent opening up under Deng Xiaoping, Terzani was finally able to move to Beijing as a foreign correspondent. He arrived in the Chinese capital in 1980 armed with a Chinese name, Deng Tiannuo. He immediately did his best to integrate and learn about his new home, but he found that the system constantly frustrated his attempts to live a Chinese life. In those days all foreign nationals in Beijing were forced to live in a “diplomatic compound” protected by armed guards, into which locals could only enter if officially invited. Informal contacts between Chinese citizens and foreigners were still difficult and risky. And yet Terzani did his best not to remain cut off from Chinese society. He rode around on a bike, sent his children to a local school, travelled around the country hard class, and got to know as many people as possible.

Predictably, Terzani’s romantic ideas about Maoism did not survive the encounter with the country’s harsh reality. In his own words:

I arrived in January 1980, and it was immediately clear to me that reality was less fascinating than dreams. I went to look for that special form of socialism that they said had been built in China, but all I found was the ruins of an experiment that had failed miserably. I went to look for that new culture which was supposed to have been born from the revolution, but all I found was the remains of the old, splendid culture which in the meantime had been systematically destroyed.

In spite of his disillusionment with Chinese socialism, Terzani started to discover something else: “I slowly came to know a splendid, human China, a China which I hadn’t dreamt much about, but a China which was much more real and interesting then the one which the government officials and the regime press presented to the outside world.”

Throughout the book, Terzani describes his trips all over the country, from Tibet and Xinjiang to Guangdong and Shandong. He also dedicates chapters to issues like the one-child policy, public executions, and the destruction of Beijing’s architectural heritage. The most unusual is the chapter written by his two young children about their experience of attending a Chinese school. Terzani’s kids, Folco and Saskia, were aged eleven and nine when they arrived in the country. In the days before fancy international schools existed, Terzani had no choice but to send them to a local school. Over the three years they spent in the Chinese capital, the two children learnt to speak Chinese fluently, but their experience of Chinese education left them decidedly unimpressed.As the children state:

In the beginning the biggest problem was the language, because it separated us from the Chinese. Once we had more or less overcome this obstacle, we found new ones. In the end we realized that the barrier that separated us from the Chinese was not so much the language but the fact that we were foreigners, since even after learning to speak Mandarin we still didn’t manage to be with them. After three years we didn’t even have a single Chinese friend. It was the teachers who were keeping the Chinese students away from us and our “foreign influence”. During our schooling, we have never been invited to the home of a Chinese, nor has a Chinese student ever been permitted to visit our home. All conversations went no further than greetings.

They go on to describe most aspects of their schooling in less than glowing terms. At the same time, they do note that their underpaid teachers were mostly very nice with them, and made every effort to teach them Chinese. Folco remembers that when he ended up in hospital, two of his teachers even came to see him and brought him some fruit. He comes to the conclusion that they are good people, but forced to follow the rules. The chapter ends with:

…our conclusions on Chinese schools are, in the end, far from positive. I, Folco, hated the spying, the criticism, the doing everything you can to save your hide. I hated the teaching system which left no space to the imagination, having to copy things down, having to learn the correct way to think, the cheating, the feeling of not being able to say what you think any more, and not even being able to think certain things.

No. Never again.”

Unsurprisingly, the authorities got fed up with this man who criticized them mercilessly and just wouldn’t stick to the script; in 1984, Terzani was arrested at the airport on the fabricated accusation of smuggling artistic treasures out of the country. Fortunately, he had already relocated his wife and children to Hong Kong. For a full month, Terzani was periodically called up to be “re-educated”, which mainly consisted of him having to write down self-criticisms, even though he was careful never actually to confess to any crime. Although the experience was obviously scary, he was at some level almost excited to get this one last chance to experience a side of China that most foreigners never got to see. In the end the authorities told him that in view of “the progress he had made in his re-education” and of the good relations between China and Italy, they would be lenient and allow him to leave the country after paying a fine.

The book ends with the words: “The fifth of March, at dawn, I go to the airport. I leave my Chinese clothes at home and I put my tie on again. I fill out all of the forms for customs in English, rather than in Chinese like I would have done in the past. I sign my name as “Terzani”. Deng Tiannuo no longer exists.”

Terzani died of cancer in 2004, after spending his last few months in the hills of his native Tuscany. No other Italian has since written about China as insightfully as he did.

* * * * * *

Reviewed by Gabriel Corsetti. Born and raised in Italy, Gabriel has lived in Beijing since 2008.

A shorter version of this review originally appeared in Gabriel Corsetti’s post Five great China expat memoirs on his blog, the capital in the north.