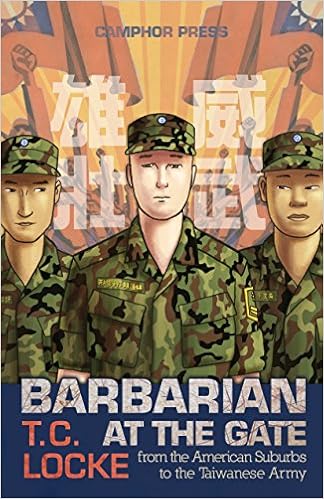

T.C. Locke (aka T.C. Lin) is the author of Barbarian at the Gate: From the American Suburbs to the Taiwanese Army. The book describes how the author – soon after gaining Taiwanese citizenship – found himself called up for two years of compulsory military service in the ROC (Republic of China) army.

Why did you decide to write Barbarian at the Gate?

It was an interesting experience, and although I sometimes kept a journal at the time, I wanted to have a more complete record. On top of that, so many people were asking what it was like that I felt there was enough curiosity and interest to justify writing a book on the subject.

How useful was feedback from friends who read drafts of the book?

The most useful feedback came from the timing of the excuses I got from them for not getting back to me on it. When I discovered that someone had apparently stopped reading the book at a certain point, it became obvious to me that that section needed work, even if they protested that their stopping was due to other, completely unrelated circumstances, as people tended to stop reading in the same few places.

Do you have any favorite parts?

The pacing of the book follows the reality of my experiences, so the action ramps down while more personal, internal conflicts ramp up over the course of the story. In that respect, I’d say that I find myself reading the last few chapters more; they are more significant, even if the initial chapters are more action-packed.

What does the book title refer to? Why did you choose it?

The original title was “Counting Mantou,” but many people as well as my agent in New York felt it was too passive and wouldn’t communicate anything to potential readers. I’d assumed there would be too many titles with the well-known phrase “Barbarian at the Gate” on the market, but I was surprised to learn that there weren’t any at the time, although there was one similar title about corporate dealings. In any case, I felt that it fit the content of the story on many levels: The “barbarian” is me, of course, and literally at the gate for reasons that are explained in the book, but it also represents certain personal demons I had to let go of in order to deal with the challenges I faced during that time.

What promotion have you done for the book?

I haven’t done any, really. A couple of Facebook posts, an interview here and there, but those were all instigated by the organization doing the interview. I’m not terribly good at self-promotion. Thankfully my publisher, Camphor Press, has added their expertise in this regard.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

There are many: Raymond Chandler, Neil Gaiman and Kim Stanley Robinson come to mind as I’ve been reading them recently.

How do you feel about ebooks vs. print books?

eBooks are convenient, and reading them is not a problem. A paperback, however, takes me back to my childhood when I would look forward to nothing more than escaping into the backyard with a book and a peanut-butter and jelly sandwich. As a result, I often read when I’m eating, so I get food stains all over everything, including my Kindle Voyage. But the smell and feel of a paperback connects with me on a fundamental level that has yet to be replicated in digital form.

Due to a lack of recruits, the Taiwanese government recently had to postpone – for a second time – its plan to end military conscription. Why do you think people are so reluctant to enlist in the army?

On the one hand you have the recruiters saying basically what they’ve always said, but on the other, you have generations of Taiwanese men, each trying to impress each other with how bad they had it in the service. So it’s not a surprise, after several decades of stories of mistreatment, abuse and other hardships, that young people are reluctant to volunteer. Although the treatment and benefits are much better today, simply telling people that isn’t enough; the military has always touted such things. The fact that they may now be true isn’t necessarily going to get people to believe them. They have to do a better job proving their worth and focus on what attracts young people to military service in the first place.

After finishing your military service, did you get called back for refresher courses?

I actually volunteered for reserve duties, which meant that I wasn’t called up for refresher courses. Of course, many men don’t get any further training after their discharge, while others might be called up several times; it seems to be rather random.

Can you tell us about the Muddy Basin Ramblers?

The Muddy Basin Ramblers is Taiwan’s first and only jug band, in which I play trumpet, euphonium and washtub bass. The band formed around 2003 or 2004, starting out with David Chen, Will Thelin, Conor Prunty and Tim Hogan, and a short while later Sandy Murray and I also joined. The six of us have been the core group ever since, though other members have come and gone. We now have nine members. Over the years we’ve released two albums, and are currently recording our third. The second, Formosa Medicine Show, was nominated for a Golden Melody and a Grammy. We’ve lasted this long as a band because we’re all close friends, and also because we’re not in it for the money, but because love the music.

If you had a large budget and a year of free time, what film or photography project would you like to undertake?

My lazy side would just travel the world and stop where I pleased to wander, photograph, play music and write, but my more practical side would probably make a film here in Taipei.

Can you tell us something about your photography?

I’ve been into photography since childhood, but I’ve never been a professional in that I never depended on it for a living. I enjoy making photos from the material of daily life; it feels more authentic and valuable than setting things up in a studio or travelling to exotic landscapes. In 2011, I joined a dozen-odd other photographers from around the world in forming the Burn My Eye photography collective, and we’ve had exhibitions at several major festivals over the last few years.

What are your favorite places in and around Taipei?

I like the older parts of the city, especially the western edge, along the river, places with a long history like Dihua Street, Dadaocheng and Wanhua. I’m happy to see a bit of a renaissance of these old neighborhoods in recent years, and hope the city can pour more resources into preserving its past rather than tearing those old buildings down.

To find out more about T.C. visit wikipedia (and follow the various links there).