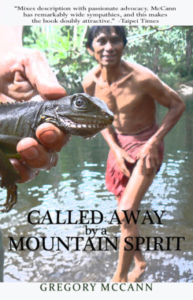

Taiwan-based American Greg McCann fell in love with the little-known wilderness of northeast Cambodia while doing doctoral research on the animist beliefs of the highlander tribes and how their belief in mountain spirits and traditional taboos translated into a form of environmental conservation. He wrote a book about his experiences, Called Away by a Mountain Spirit, and embarked on a crusade to promote and preserve Virachey National Park.

What first attracted you to doing research for your Ph.D. in Cambodia?

I wanted to find a place in Asia where the aboriginal people had not yet been converted to Christianity, as they have in Taiwan, Vietnam, and many other countries. Due to decades of civil war and Vietnamese occupation, missionaries hadn’t made much headway in Cambodia. I wanted jungles and animism, and when I learned that there was a place called Virachey National Park in Ratanakiri province where ecotourists could do a 7-day trek with minority guides and porters that included village homestays at the edge of the jungle, I knew this place was for me.

What were the travel highlights of those research trips?

Being woken up in my hammock by the cry of gibbons each morning. Nothing compares to that. A close second would be the view of the jade-green jungle mountains that form the Cambodia-Laos border set against the charred-yellow Phnom Veal Thom Grasslands in winter. It’s a sight that rivals the Himalayas, and one you would not expect to find in Cambodia and in the middle of the jungle at that. After two days of trekking you emerge from a shadowy, sometimes claustrophobic world of a closed canopy forest onto this inexplicable rolling savannah cast against the high border mountains. Every time I see it, it takes my breath away. Third would be getting drunk on homemade rice wine in the villages with the locals while learning about the spirit mountains and the crazy stories that have happened in what is now called Virachey.

What is so special about Virachey National Park?

It’s one of the last places of Indochina where large mammals can still be found. Much of the Annamite Mountains in Vietnam have been defaunated—what a horrifying word and concept. But not Virachey, not yet, though it has probably lost all its tigers and most of its elephants. In addition to gibbons, the place is swarming with clouded leopards, binturongs, hornbills, and much more. Virachey offers the best ecotourism experience in mainland Southeast Asia, in my opinion, with treks of up to two weeks on offer. Think about that—two weeks in the jungle swimming in rivers for your bath, gibbons for your alarm clock, and whisky in bamboo cups for your nightcap. To me it’s paradise. At 3,325 square miles it is Cambodia’s largest national park, and as part of the Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, it is one of the most biologically rich and threatened places on the planet.

What threats does the area face?

The threats are myriad and hydra-headed. Poachers-loggers-miners (they are often all three of these things wrapped in one) from Vietnam who can just walk over the forested border into Virachey. They lay hundreds of snares, shoot gibbons and douc langurs out of the trees, build their own roads—they are a scourge like no other. I’ve used Google Earth to find new dirt roads coming right up to the Virachey border in Laos, so we have Lao poachers penetrating the park from the north. Then there are local Cambodian loggers and poachers who do the same, so the threats are coming from all angles at all times, non-stop. We have one particularly tenacious poacher photographed on two different camera traps over a month apart, most likely a Vietnamese. Criminals like him will not stop until the last animal has been snared or shot. And then there are the Economic Land Concessions sold by the government—chunks of the park liquidated for profit. How can you stop that? The government owns the park, and they can do whatever they want with it. Encroachment by local farms. The threats are endless.

How do the local people feel about the park?

When Virachey was gazetted as a national park in 1993 the highlanders living inside of it were forced to move down to Sesan River, and some didn’t like that. The World Bank sponsored a protection and capacity building program from 2004–2008 and during that time the rangers were better equipped and made arrests, and hunters didn’t like that at all. But today there is little enforcement and patrolling so locals just go in and do whatever they want. I think most local people have forgotten that it’s a national park. Anarchy reigns.

Since publishing Called Away by a Mountain Spirit you’ve returned several times. Can you tell us about those trips?

In that book I describe one mountain in particular that captivated me—Haling Halang, which sits right on the Cambodia-Laos border a good 4–5 day one-way trek. Getting to the base of that mountain in the middle of thick jungle and finding a way to the top became an all-absorbing obsession for me, and two years after the publication of Called Away we finally did make it to the top. To the best of my knowledge, me and my team were the first Westerners to ever set foot on it. It was the first time for the highlanders and the rangers as well. Two Brao porters refused to summit, saying they would be cursed by the spirits if they did. I had to fight back the tears when we reached the top. We set up two camera traps on the ridge line which, in addition to clouded leopards and sun bears, produced the third record of spotted linsang in Cambodia, the second record of yellow-bellied weasel, and the first photographs of black-hooded laughingthrush for Cambodia. So now, instead of doing ethnographic research and writing down the old stories and legends, my efforts have turned to this wildlife survey.

Do you have any plans to update the book or write a second one?

I would like to update it but I can’t see getting to that in the near future. I’ve started work on a second book, which will be about my subsequent trips to Virachey, as well as Thailand, where we also did camera trapping, and Sumatra, where I will begin a new project this summer. A working title I have going is Called Away by a Siamang Gibbon.

Why did you use pseudonyms in the book?

I thought that some of my Cambodian friends would not want to see their names in a book that criticized the government in any way. That was the main reason. I still believe it’s better for them.

What’s your involvement with the conservation NGO, Habitat ID?

I am the co-founder and Project Coordinator of Habitat ID. Basically I do everything: fund-raising, camera-trapping, organizing the expeditions, promoting ecotourism, getting cash and resources to the rangers when I’m not there, writing articles to raise awareness, coordinating with other NGOs. The list goes on, and it’s all unpaid, but at least I get funding for these trips, otherwise I couldn’t do them. For this upcoming trip to Sumatra I hunted down two Indonesian bird experts and convinced them to join us—at their own expense. It is so great having birders with you in the forest not only because they can identify every tittle tweet you hear but they can produce a species list in very little time, which is tremendously useful.

What animals have been captured on camera? What wildlife is missing?

We’ve camera trapped just about everything we should have, with a few notable exceptions: tigers, common leopards, elephants, pangolins, and, strangely, crab-eating mongoose. The first two I’d say have vanished, not just from Virachey but gone entirely from Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Gone! We have got lots of clouded leopards, marbled cats, gaur, dhole, Asian black bears, sun bears, douc langurs, and much more.

What are the ethics of releasing information about endangered wildlife? Some critics say it informs poachers but it’s hard to imagine poachers aren’t already aware of what animals are in an area.

I got some camera trapping lessons in Thailand’s Thap Lan National Park before I started doing it in Virachey, and the guy who invited me and showed me how it’s done—a veteran in the conservation business—is totally against sharing camera trap photos. I can see his point in regards to tigers and rhinoceros. If those turned up in our cameras we would never share them. But I don’t see anything wrong with publishing photos of more common species such as gaur, clouded leopards, sun bears, and macaques. The hunters all know very well that those animals can still be found in the forest. We are not telling them something they don’t already know when we post a photo of a binturong, a sambar deer, or a leopard cat. And remember, poachers did a damn good job of hunting out all the tigers and common leopards well before camera traps were deployed. So, for certain species, I’d agree that photos shouldn’t be made public, but I don’t agree that all camera trap pictures must be kept a secret. They can be used to attract the interest of other NGOs and individuals who want to help out, and people have helped out because of them.

Which people and organizations have given the greatest support to conservation projects in Virachey National Park?

No other NGOs besides Habitat ID work in Virachey at the present time. In fact, the last organization that did anything there was Conservation International back in 2007. In early 2008 the World Bank, WCS, and WWF left the park and never returned. I’ve been working on getting conservation NGOs to come back or begin a new project there, but so far to no avail. I think the place is considered too difficult, too complicated with the Lao and Vietnamese borders, too lawless in Ratanakiri. It’s a shame. However, concerned individuals have stepped forward and lent us a hand, donating camera traps and memory cards, participating in a “camera trap ecotourism” program that I designed in which tourists pay for the experience of trekking to these remote areas where our cameras are deployed—areas where regular tourists wouldn’t go—and changing the memory cards and batteries for us. This has helped create work for the local people who take them there, it has generated some income for the park, and it also pays for a ranger patrol as these activities require the presence of a national park ranger. Maybe that’s the future of real on-the-ground conservation: motivated individuals, motley crews of wildlife enthusiasts, ragtag bands of underfunded scientists.

Is there any prospect of a transnational park covering Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam?

I like this idea but when I mentioned it to a prominent scientist he replied that this would just add another layer of complexity to what the park authorities have to do. He said they already have major difficulties coordinating at the provincial level between different protected areas, and coordination between two different provinces in Vietnam is next to impossible—and as a result Vietnam’s protected areas are in a shambles. Don’t even mention national coordination. So, if we ask the authorities to try to cooperate at the international level the whole system would probably come crashing down. I’m afraid he’s probably right.

What recommendations do you have for people looking to visit the park? What’s a suitable itinerary for a week? Where can they get information?

Honestly, the best thing to do if you want to do a serious trek in Virachey is to send me an email and I will put you in touch with Mr. Leam Sou, Virachey’s best guide. My email is: greg.mccann1@gmail.com If you’re going to travel all the way up to Ratanakiri I highly recommend the 7-day Phnom Veal Thom Grasslands trek. Add an extra day and you can camp at a sublime waterfall pool called D’Dar Poom Chop, which translates to “Broken Pineapple Rock.”

Can visitors get to the park from Siem Reap or is it better to arrive in Phnom Penh?

Today either one is fine. Buses leave each morning from both Phnom Penh and Siem Reap for Ban Lung, the provincial capital of Ratanakiri province.

Do you have any recommendations for books on wildlife conservation in Southeast Asia?

The Last Unicorn (2015) by William deBuys is breathtaking. It deals with a trip to a protected area in Laos, also in the Annamite Mountains like Virachey, and is so eloquently written and informative that I feel it belongs up there with the best books by George Schaller. I love Alan Rabinowitz’s books on Burma (Beyond the Last Village) and Thailand (Chasing the Dragon’s Tail). I also seek out older books that describe Southeast Asia before chainsaws, massive plantations, and hydroelectric dams showed up on the scene, titles like Indo-China and its Primitive People (Vietnam) by Henry Baudesson, Laos and the Hilltribes of Indochina by F. J. Harmand, and Green Silence (Indonesia) by Ivan T. Sanderson. It was a different world then, with tigers snatching porters right off the trail, and when I read books like those I always feel like I was born 150 years too late. I’d also like to recommend one truly stupendous and highly readable tome: The Retreat of the Elephants: an environmental history of China by Mark Elvin.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

Ivan T. Sanderson, Frank Kingdon-Ward, Anthony Burgess, George Schaller

What are some of your favorite fiction/non-fiction works?

Fiction: The Malayan Trilogy by Anthony Burgess, and anything by Dostoyevksy. For non-fiction, in addition to the titles I mentioned above, I’d list: Tropic Fever: The Adventures of a Planter in Sumatra by Ladislao Szekely, Impressions of the Siamese-Malayan Jungle by Hans Morgenthaler, Mystery Rivers of Tibet by Frank Kingdon-Ward, Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life by Ivan T. Sanderson, Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest by Wade Davis, Raffles and the British Invasion of Java by Tim Hannigan, for starters.

What are you working on at the moment?

Finalizing the details of the Sumatra expedition, editing a book chapter I have about Virachey in an IUCN-sponsored Routledge anthology, editing a scientific paper on the small carnivores of Virachey, and working on getting a new NGO up and running that will be all about clouded leopards.

Called Away by a Mountain Spirit is available on Amazon.