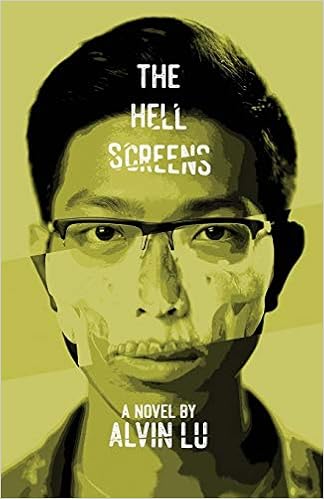

Alvin Lu, a second-generation Taiwanese American who was born and currently lives in San Francisco, is the author of The Hell Screens, a stylish thriller set in Taipei. The protagonist is Chinese-American Cheng-Ming, who is obsessed with a serial rapist-murderer known as the Taxi Driver Killer (aka K), who is terrorizing the city. The police are constantly closing in on the killer but are never quite able to catch him. K is in frequent communication with the media, scorning his pursuers and taking pleasure in his infamy.

The Hell Screens was originally published by Four Walls Eight Windows in 2000, and was reissued in August 2019 by Camphor Press. The first edition received a lot of praise (when your novel is reviewed in the New York Times Book Review with a comparison to Nabokov, then you know you’re doing something right). Like many good books which find themselves out of print, The Hell Screens was a victim of a musical chairs succession of acquisitions, with publisher Four Walls Eight Windows acquired in 2004, and this new publisher in turn acquired in 2007, and then the third publisher bought by a private equity firm. But enough about the woes of the publishing industry; time to talk with Alvin Lu.

* * *

What’s your connection to Taiwan?

My parents immigrated to the U.S. from there. I spent childhood summers in Tainan with my grandparents and extended family.

What was the inspiration for the novel?

I lived in Taipei for about a year, keeping afloat with odd jobs of the expat variety. This was in the early 90s. People who were there will probably remember the atmosphere as being very charged. Everyone was placing their bets.

What do you mean by “placing their bets”?

What’s the opposite of “desperate”? Wild hope? People trying to get in on the last wave of the bubble, wringing whatever they can out of it, taking their chances on stocks or starting their own crazy business, before the window closes. But also politically. There were mass demonstrations, armored vehicles and soldiers in the streets, that kind of stuff.

I had a lot of time on my hands and spent it walking around and on buses and ran into some interesting characters. The writing of the book took place some years later. San Francisco, where I was living, was charged, in a different way. Everyone was placing their bets, too. This was dot-com 1.0, which isn’t like now. Images and a certain mood I was trying to capture made it into the book.

It seems pretty obvious reading The Hell Screens that the infamous crime rampage of Chen Chin-hsing in 1997 was a strong influence. At that time there was something of a violent crime wave – amplified in the public imagination by the media – and then came Chen’s trail of kidnapping, robbery, rape, and murder: an eight-month crime saga that shook the country. And the climax saw Chen taking an expat family from South Africa hostage, a drama that was played out live on national television.

I spent parts of 1997 in Taiwan. I was writing Hell Screens by then and used my trips to corroborate parts of the book (which I wasn’t really thinking of as “a book” anymore at the time, more like a personal project). It was transforming from a “this was what happened”-type narrative into the journal-entry “this is happening to you now” form it ultimately took on. I think I kind of improvisationally mixed in the daily news into the story, to jolt it into immediacy. That crime wave was palpable then, like you could make wallpaper out of the headlines. In that sense, the stuff about K taking over the mind space of the narrator is “what really happened.”

What does the the title The Hell Screens refer to?

It comes from Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s (the guy who wrote “Rashomon”) “Hell Screen,” which was one of the sources I was going back to while writing, although probably the more direct inspiration were the two companion pieces in the collection it was part of, “Cogwheels” and “A Fool’s Life,” which are about a mind disintegrating into the backdrop of a dense urban environment. But probably the real, and more lasting, influence was the language of those two stories, not so much Akutagawa’s as his translators’, Cid Corman and Will Peterson, who had him speak like a midcentury bohemian Kyoto expat.

Some of my favourite writing in the novel – and where the weirdness gets dialled up a few notches – is when protagonist Cheng-Ming visits a temple in the countryside. Is this temple based on an actual place?

No. It probably came from my reading Pu Sung-ling. There’s that same haunted temple that appears in every story in Liaozhai

The Hell Screens has a hallucinatory quality to it, part of which comes from the trouble the protagonist has with his contact lenses. Did you wear contacts when you were writing the novel?

Yes. I hate wearing them. It’s always been a struggle. This probably comes across in the novel.

The Hell Screens is a very visual book. Do you have a background in art?

I am probably coming at it from the worlds of comics and film. I was a film reviewer (which used to be a paying job) at the time I was writing the book.

How did it feel going back to The Hell Screens and working on it after about two decades? Were you struck by the daring, the intensity, and the quality of the writing?

Predictably, quite weird. I’d gone into this determined to treat it as nothing more than a reprint, but Mark convinced me there were bits and pieces that needed clarifying. I have to thank him for that, because that’s how I stopped seeing it as an artifact from my past and more as a work living in the present. It holds up well that way, I think. I was afraid the chances I thought I was taking weren’t as big as I thought they were—but, wow, it’s pretty wild, and is actually rather relentless about it, and that made me happy.

Are there any works from fellow Taiwanese-American writers you’d like to recommend?

Mouth by Lisa Chen is a remarkable collection of (I am guessing it is) poetry. I’m not sure how much of Karen An-hwei Lee’s background is Taiwanese (sorry, Karen!), although the writing itself seems to come somewhere from around there. Her two novels, Sonata in K and The Maze of Transparencies, seem like they were written by magic. Shawna Yang Ryan, who’s a very different kind of writer, wrote a beautiful and weird novel I first came to through my other regional interest, rural California. It’s hard to pull off ghosts in California (I tried), but she does some great work with them in Water Ghosts, as well as anybody since Ambrose Bierce, I think. And she went on to write Green Island. That book is of course about Taiwan, but I appreciate the fact that the central scene the entire epic narrative swirls around takes place in, of all places, Willits.

Who are some of your favorite novelists?

[Looking around]Hisaye Yamamoto, who’s really underrated, and Amiri Baraka (underrated? overrated? nobody knows?). Neither of them are really novelists, though. Susan Daitch (underrated). Stephen Beachy, who wrote a great novel called Glory Hole (in which I am name-dropped), turned me on to Ricardo Piglia and Ascher/Straus. The Other Planet might be the best book, like, ever.

Are you a fan of Lovecraft’s work? Later this summer, Camphor Press will release a translation of Lovercraftian tales from China.

Wow, that is awesome. I really want to read that. I used to submit horror stories to Twilight Zone magazine. Ted Klein, who was the editor there, never published me, but he’d very generously (considering I was a teenager) write me back long letters. He’s one of the great horror writers himself, by the way—I like the novellas in Dark Gods best. I remember him warning me off a life in publishing, advice I didn’t end up following. He introduced me to Lovecraft in those letters (which looking back I think was a self-consciously Lovecraftian move on his part). I remember reading At the Mountains of Madness first (the Del Rey edition with the scary paintings by Michael Whelan) and thinking, “Man, this is totally blowing my mind.” One of the more memorable reading experiences of my life.

* * *

The Hell Screens is published by Camphor Press. It is also available from various other outlets such as Amazon.com.