I don’t review poetry. Well, until now. I’m breaking that commandment in posting this review of Scott Ezell’s outstanding poetry chapbook, The Front Lines of the War. The problem with reviewing poetry is I lack the knowledge and ability to appreciate and describe it, and I’m not a big fan of modern poetry; there’s too much bad, lazy, self-indulgent material out there. However, for Ezell – whom I’m never met – I’ll make an exception. A Far Corner (2015), which chronicles his time in the coastal village of Dulan in southeast Taiwan, is full of magnificent passages, some of the best writing I’ve seen on Taiwan. (My Bookish Asia review can be found at: A Far Corner.)

In the The Front Lines of the War, Ezell describes a visit to Shan insurgents in the northeast of Burma during a government army offensive. The poetry starts off as a stripped down travelogue.

Arrive Hsipaw after 12-hour bus from Mandalay,

army trucks carry soldiers and guns through the night,

a teenage mother drives a motorbike

through the diesel haze,

one hand on the throttle

one hand holding a baby to her breast

as eighty miles away

a rebel army digs into the hills

waiting for a government attack

We’re along for the ride with the author on a clandestine trip to the Shan State Army-North. From Lashio he heads to the rebel headquarters at Wan Hai, passing government checkpoints along the way. The driver:

… hands me a cap to cover my head,

a vain gesture of disguise

since I hulk like a yeti in the shotgun seat,

Scott Ezell is not exaggerating – he is exceptionally tall and has no choice but to stand out.

The driver motions me in back

and covers me with a tarp—

he slows to a stop and I hear

interrogation voices in Burmese.

We drive half an hour more

he pulls over and uncovers me—

I emerge to rice and corn fields

golden in the sun,

haystacks twenty feet high

and limestone karsts in all directions

like breaching whales

rising from the plain.

Wan Hai lies at about a thousand meters and is a bucolic landscape of hills and rolling fields lit by the golden colors of late autumn. This is November and the weather ideal for a visit, and for the Tatmadaw (Burma Army) operations – they’re two months into an offensive which has included shelling, air attacks, and ground troops. Ten thousand refugees have fled the fighting.

Ezell’s “Shan State Suite” has six sections, and part four ends as he and the Shan are waiting for an attack.

Farmers take their oxen out to graze

on short stiff stalks of

harvested rice fields,

bells around their necks

toll in the autumn air

between two lines of hills

between the front lines of the war.

That last line is used as the title of the next section “The front lines of the war,” which is the title of the book. Here the writing intensifies. Anger flared earlier, but now it’s with full force:

I was on the front lines of the war

I saw soldiers eating dirt and grass

I saw the women they left behind

and children with flies in their mouths

Livestock wandered through the battle zone

Metal made nests in trees

Mortars and machine guns were pointed at the sky

Soldiers made love after dark

Kitchen boys ate scraps

and waited naked for their uniforms to dry

I heard the arms manufacturers laugh

over paté and wine

I saw them clean blood from their teeth with matchsticks

I saw hair and clothes on fire

while governments sat at 5-star tables to negotiate

Ezell then moves from the details around him to the abstract madness and horrors of war.

I saw grass turn gray like hair

I saw monkeys snug neckties and drive to work

to pick fleas from each other’s fur

I heard rain on a metal roof

and animals howling in the slaughterhouse

I heard earthworms chuckle in time

with a symphony of machine gun fire

It’s powerful, sustained masterful writing, mesmerizing imagery and cadence. In part six, his focus moves more to the politics and economics behind war, and he carries that into the next long poem: “Civil War.” I would quote a striking passage from it, but Ezell has used it on the chapbook’s back cover (which you can see at his website).

Toward the end of the nest poem, “Shatter Zones,” Ezell employs maritime metaphors – there are multiple uses of “sea.” It’s very personal writing, and you feel the author is overwhelmed and perhaps a little lost. I was confused earlier in the book, with “Moitessier,” the second piece in the Shan State Suite – with reference to a nautical figure (I had to Google “Moitessier” – he was a French sailor famous for his involvement in a 1968 solo round-the-world yacht race around the world). I feel this takes us away from the Shan States and would have been better omitted.

When I agreed to review Ezell’s poetry book, I thought I would – to make up for my lack of poetry chops – give some background to Burma’s long-running war with the nations many ethnic peoples. However, it soon became obvious that it was just too complicated. Even restricting things to Shan State, there are just too many ethnic groups, too many insurgent armies, and too much history. More than half a century of fighting, of ceasefire agreements made and broken, of alliances forged and broken – these do not make for easy summary or reading. And then it struck me; the utility of poetry in telling the essential truth of the tragedy of Burma’s borderlands.

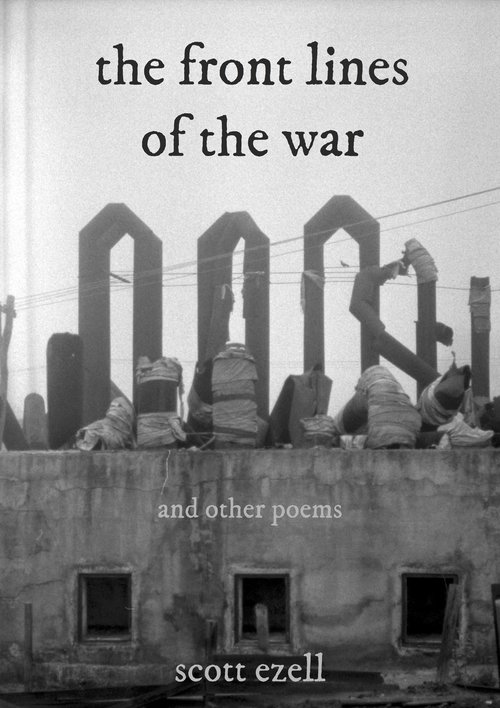

The Front Lines of the War packs a punch beyond its small size. It’s gritty and evocative, and has huge empathy for the region’s people, and righteous anger at the human suffering alongside resource extraction. The book has a lot of heart, more than suggested by the bleak cover shot of a derelict tin smelter. The pictures in the interior – which were also taken by the author – are of the Shan people.

To buy a copy of The Front Lines of the War, contact the author through his website: http://www.scottezell.org