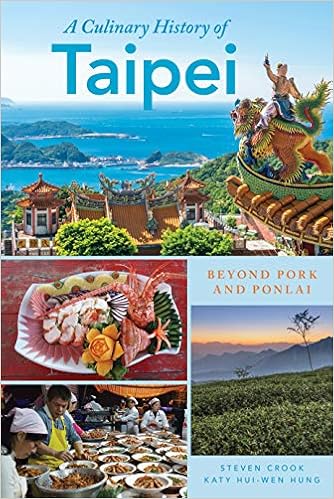

Katy Hui-wen Hung is co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai. Co-written with veteran Taiwan writer Steven Crook and published by Rowman & Littlefield, the book is a landmark work, one of the most significant English-language titles on Taiwan published in the last decade.

I always have trouble replying to foreign friends and family members when they ask: “What is Taiwanese cuisine?” What’s your stock answer for this?

What is Taiwanese Cuisine? Taiwanese cuisine has been described by many Taiwanese (and Chinese) culinary professionals as ‘soupy’ and ‘small’ – adjectives I personally interpret as meaning ‘simple’ or ‘unpretentious’. In the old, poorer days, boiling in water was the only practical and economical way to cook up a family meal. Soups served with the meal made swallowing rice (or other carbohydrates) easier. The ‘small’ element comes from being homely and satisfying for people you cared for.

Taiwanese cuisine is firstly and most notably associated with influences from the southern provinces of China, in particular Fujian. At the same time, Taiwan’s status as an exceptional overseas outpost of Japanese cuisine is a consequence of both history and proximity. After 1949, retreating mainlanders changed the culinary character of every Taiwanese city. Many exiles who had no money set up food stalls; the more successful ones upgraded themselves into proper restaurants.

After 1950, US aid in the form of wheat and soy transformed eating patterns, and was a factor in the emergence of beef noodle soup and pineapple cake, now both regarded as iconic Taiwanese foods.

Our subtitle suggests Taiwanese are now eating “beyond pork and ponlai”. Pork is the major protein, and every part of a pig can be made into a dish. Lard was an essential ‘Taiwanese flavor’ until the recent promotion of healthier cooking styles. The Japanese brought beef-eating habits to Taiwan, slowly overcoming the taboo against slaughtering cattle (because the animals were needed for agriculture). Even now there is a taboo against serving beef at a traditional Taiwanese banquet.

Of course, 50 years of Japanese rule had an impact on other facets of local dietary culture, even altering the type of rice eaten with meals. During the colonial period, the indica rice cultivated by early Han settlers gave way to stickier ponlai strains developed to suit the Japanese palate. Today, there are many Taiwanese dishes that it would be unimaginable to eat without a bowl of ponlai rice.

Taiwanese say: ‘Live by the Sea, Eat from the Sea.’ Taiwan’s geographic location means there is no shortage of seafood. Indeed, Taiwanese eat a lot more seafood than Japanese or Americans.

The most important factor in Taiwan’s agricultural success has been the dedication of the farmers themselves, resulting in an abundance of fruits and vegetables. Quality and taste, as well as choice, has seen phenomenal improvement compared to 30 years ago. Sweet potato leaves were bitter and only good for feeding pigs; now, they’re on the fine-dining table as healthy greens. The tree plum – formerly sour and eaten only by birds – is now an ingredient in dessert recipes. Local fresh fruits are available in every season; Taiwan’s pineapples and mangoes are among the best in the world. The fruity notes in Kavalan whisky seems to be one of the reasons why this Taiwan-created and -made whisky has won such acclaim. Taiwanese people’s love of fruits goes back to the Qing dynasty when a mango ‘Penglai’ sauce was used for pickling or cooking fish.

To single out the items that make Taiwanese cuisine ‘unique’, my personal choices are fruit and Taiwanese Red Label rice wine. Taiwanese rice wine is a ubiquitous and essential ingredient, and is a key part of popular three-cup dishes. The high-temperature cooking method for three-cup dishes is also typically Taiwanese.

A Culinary History of Taipei is part of publisher Rowman & Littlefield’s Big City Food Biographies series. Is it fair to say the book is really a culinary history of Taiwan, with the “Taipei” title just so it fits in with the city focus of the series?

Not that straightforward. It was what we had to do to make sense of the book to target readers. I had discussions very early on with Professor Albala, senior editor, about my concern – that Taiwan being so unknown and underappreciated, not introducing Taiwan culinary history simply would not have made sense. I feared our efforts would be futile. Taiwan is ‘off-the-radar’, undiscovered, let alone its fascinating history, or its capital city

However, readers would have noticed – chapters 4 to 10 focus on Northern Taiwan, other parts of Taiwan covered only when necessary to enhance Taipei. Chapter 7 exclusively focuses on Taipei landmark restaurants.

You explained earlier that “ponlai,” which appears in the subtitle Beyond Pork and Ponlai, is a kind of rice. Can you tell us something more about it?

Ponlai is the name of a category of flavorful, high-yield rice varieties perfected in Taiwan by researchers during the period of Japanese rule, which lasted from 1895 to 1945. Ponlai rice is sometimes translated into English as “Formosa rice.”

The word “ponlai” is derived from a pair of Chinese characters pronounced pénglái in Mandarin. In both Chinese and Japanese legend, Pénglái is a mythical paradise, and the name has been fondly applied to Taiwan by writers and poets who recognised how much this bountiful island could provide for its human inhabitants. A couple of examples of usage are:

- Tsai Peihuo, The Taiwan Autonomy Song 1925 – “… On enchanting Pénglái (Formosa) where our ancestors settled down…”

- Yang Kwei, The Newspaper Man 1934 – “The deck of Pénglái (Formosa)…”

A Culinary History of Taipei is the first book in the series for Asia, which is quite an honour How did this book project come about?

Marlena Spieler, an American award-winning food writer of more than 70 cookbooks who is now based in London, planted the seed by introducing us to Ken Albala, the series editor. She, along with a number of European food writers were invited by Taiwan Tourism for a round-the-island culinary tour about four years ago. I connected with her on Facebook; she being totally impressed and fascinated by Taiwan’s vibrant food culture and fabulous resources encouraged me to try writing about it for Ken’s semi-academic City Food Biographies Series. She thought that could be the only way to raise awareness on Taiwan to the world through food and history. At that point, Ken had not considered Asian cities, but was open and supportive to Marlena’s suggestion.

How did you and your co-author, Steven Crook, divide up the work on the book?

Based on each other’s strengths. Mine is in rich family history and networking. Steven’s obviously in his 20 years’ freelance writing on Taiwan travel and culture. We worked out that my main focus should be on special foods; teaching, sharing Taiwanese cuisines; dishes and recipes. For big chapters like Chapter 4, we compiled, shared info and research materials, and Steven shaped it at a final stage before submission.

What was your primary goal in writing the book? What most do you want to present to audience?

My initial goal was actually to relearn Taiwan. Having lived abroad since the late 1980s, I appreciated this was a fantastic and probably once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to relearn my home country and to embrace the phenomenal transformations since I had been away. That was my motivation to take on the challenge. I don’t have a background in writing, and this is my first book.

Taiwan’s abundant resources. Taiwan’s complex gastronomic history and traditions. And Taipei’s vibrant food culture and evolving food scene in making it one of Asia’s best food destinations.

What did you learn when writing this book?

I discovered I had an ability to discover. I seemed to have an observational skill in locating Taiwan’s worth, a drive to explore, and finally to share. I discovered nice surprises and sometimes important surprises, I was told. I consider myself highly cross-culture. I think that contributes hugely to my work.

Did your research overturn any of your assumptions or preconceptions about the subject?

Yes, many. A prominent example is Indigenous cuisine. However, my assumptions or preconceptions came from the lack of development of the cuisine itself. I wasn’t uninformed or outdated, simply there wasn’t much to learn and I do think I came in the right time exploring and the book came in the right place showcasing Taiwan’s indigenous food.

Having taken a close look at Taiwanese foodways, are there any trends or habits which impress you? And any that alarm you?

Bando clearly – in the book there is a large section on Taiwan’s roadside feast tradition. And I spent over a year observing and learning from a banquet maeastro. Reviving old-time-flavor is a trend now I would say, and I have first-hand experiences from writing the book. The young generation want it and are interested in it – thanks partly to the success of the film Zone Pro Site: The Moveable Feast (2013).

Innovative and culture-creative food and restaurants alarm me. Both should be created based on solid food knowledge. But it’s not working like that with Taiwanese – people are looking for shortcuts to make short-term money which results in a ‘quick’ and fickle industry.

Taiwanese also tend to be a little ‘superstitious’ in health food, sometimes for little or no scientific evidence. A South African ‘miracle-leaf’ that cures cancer sworn by many, for example.

What did you enjoy most about this project? What gave you the greatest sense of achievement?

To get people to talk and share their stories. And with their permission – to share to a wider audience. I always say “Good things should be known. Good stories should be shared”. To interpret and process what I observed and experienced into my own bag gave me a great sense of achievement. It is a lot of hardwork, and sometimes frustrating, but I can proudly say “This is mine”.

Recently I decided to start a blog (https://katyhuiwenhung.blogspot.com) to share my discoveries and stories. The layout is basic and I am yet to reconstruct and improve – my priority at this stage is entering posts and really just enjoying what I do. I won’t post if I don’t enjoy it. I don’t limit to specific subjects – anything interesting. The more popular posts so far are, for food, “Mongolian BBQ History” and, for history, “Grand Hotel Taipei”.

What kind of reaction did you get when approaching people to interview?

I have not had problems. I think I planned and chose my candidates sensibly, and I briefed them with my intention and goal. Many times they didn’t turn out to be suitable candidates, but being approached by me was never a problem.

How did you become a food enthusiast?

Ha! I have not become a food enthusiast. If I am one, then 95% Taiwanese are too! It is simply food is a popular topic here. A subject everyone has something to say!

As I said, my motive is to relearn Taiwan. And giving this opportunity and food an essential and fascinating part of human history. I relish and thrive in exploring FOOD AND HISTORY.

You’ve helped a number of big-name foreign food writers such as Andrea Nguyen and Robyn Eckhardt on their Taipei food assignments. What aspects of the local food scene were they most interested in?

Andrea Nguyen was specifically interested in Tofu, for her book ‘Asian Tofu’. It was her first and only time in Taipei. She was impressed by the quality and varieties of Taiwan tofu – in particular soy bean creations in vegetarian food. She thought it was phenomenal.

Robyn had several trips to Taiwan. Her interest was street food – but made it clear, not night market gimmicks but morning-day markets – the peoples’ food. She thought Taipei is one of Asia’s best food destinations in its balancing old and new. She was also impressed with Hsinchu and Tainan snacks and treats.

* * *

A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai is available from Rowman & Littlefield, Amazon.com, and various other retailers.