Reviewed by Frank Beyer.

This novel details the life of Isham Cook, pen name of an American writer who has lived in Beijing for many years. It isn’t a straightforward read; Lust & Philosophy follows Isham through a number of coming of age experiences in different countries and they’re not in chronological order. Those who like to be outraged will speculate which sexual encounters described are really autobiographical. But that would be missing the point, which is: sex is suppressed to a pathological degree, while other pleasures are restricted and demonised too. Isham’s retelling of Genesis in chapter 16, probably explains best what he is on about, how he would like to see things turned upside down:

They made love. Adam had his first taste of pussy. Eve had her first orgasm. Up till that point it had merely relieved an itch, something they had scarcely been aware of doing, but now it clicked – how cool sex was. They realized as well how much time had been lost. Their anger grew as they understood their predicament, and the solution likewise became clear. Ialdabaoth was powerful only as long as he nourished himself on others’ ignorance and fear. But why run away from Eden only to let Ialdabaoth remain in control? That very night as he slept, Adam and Eve slit his throat. They stuffed his penis in his mouth, popped his testicles into his eye sockets and smoked his eyes.

Another major theme is that we live in societies full of inexplicably obstructive rules and individuals. My favourite quote in the book is:

“Why is it people routinely excel at being stubborn and difficult while avoiding at all costs whatever is easy and wonderful?”

The narrative follows the whims and the wide-ranging interests of the erudite Isham; he finds links that leave mere mortals behind. The starting point is Isham’s spotting of an alluring Chinese woman he dubs Cookie on a Beijing street. Isham’s descriptions of Chinese streets aren’t plentiful in this work, but I appreciated what there was:

The narrative follows the whims and the wide-ranging interests of the erudite Isham; he finds links that leave mere mortals behind. The starting point is Isham’s spotting of an alluring Chinese woman he dubs Cookie on a Beijing street. Isham’s descriptions of Chinese streets aren’t plentiful in this work, but I appreciated what there was:

A Japanese restaurant on the corner. Hair salons, massage parlors, donkey meat eateries, groceries, a popular Manchurian restaurant. A Hunan restaurant. A Xinjiang restaurant. More hair salons along the street’s darker western stretch before it linked back to Changwa Middle Road, these salons being of the shabbier variety, with handjob services. Another Japanese restaurant on the corner, a teahouse on the facing corner.

He wants to approach Cookie and muses on the fraught undertaking that is addressing a stranger on the street. He is hopeful she’ll stop and he can achieve his goal of sexual conquest. On the other hand if she is on her way to work he might be ignored.

But I cannot deny the deeply ingrained norms of behavior we are all burdened with: the same unconscious compulsion that makes us swivel around when the policeman hails us keeps us pointed straight ahead on our way to work.

Before he could become Isham Cook the writer who works at a university in Beijing and pursues Chinese women, he had to throw off an oppressive superego that controlled him through fear rather than guilt. Freud thought the superego came from the father – a strict father could mean a rigid moral code – and great guilt resulted when it was (almost) inevitably transgressed. Society too functions like a superego telling the individual what to do. In the contract for being a member of a civilised society is a clause stating we need to sublimate much of our natural aggressive and sexual drives into work and art. Those who have difficulty with this (nearly everyone at some stage or another) will get into trouble and damage their standing. In chapter two we meet the nine-year-old Isham, and after an exposition on battleships, one of the least entertaining asides in the book, we learn that his divorced mother has married an ex Jesuit priest named Joe. Also in this chapter Isham is sexually abused at summer camp – his take on the incident is predictably different from what you might expect. Joe becomes the overbearing superego in Isham’s life:

The harangues take place every three weeks or so, after a buildup of hostile silence. I never know what he is angry about until the harangue begins, but whatever it is, it always concerns the same petty infractions. They are permanently registered on a yellow pad of legal paper, the list filling up more and more of the pad over the years, so he can flip through the pages to remind me how many instances of the same infraction were previously committed, dates recorded in the margins. Nothing is ever forgotten or forgiven.

Joe reminded me of Dwight, the evil stepfather in Tobias Wolff’s novel, This Boy’s Life. Dwight, an alcoholic like Joe, was well played by Robert De Niro in the movie. It’s a fair bet there won’t be a film version of Lust & Philosophy – a shame. While Joe is important, Isham’s mother is a complete non-entity in the novel.

I can imagine Cook writing a Swiftian satire where he travels in imaginary societies with very weird sexual mores. The best satire in this book is about the world of academia at the University of Chicago. He observes, quite correctly, that most academics are not intellectuals. De Sade is another obvious influence. I haven’t read any of de Sade’s famous novels of extreme sex and cruelty like The 120 Days of Sodom but only a short story collection in Spanish translation titled Cuentos. I bought it in Buenos Aires, where classics are available cheaply. The cuentos, or tales, have very little which is sexually explicit, but I noticed that de Sade is an expert at showing the corruption of priests, politicians and aristocrats. Like the Marquis de Sade, Isham leads a life that would shock the moralists of his time, while he takes aim at the hypocrisies he sees in society. Cook isn’t de Sade though; he isn’t rotting away in a prison – there is no sadism here, just sexual lust and frustration more extreme, or at least honestly revealed, than in the regular individual.

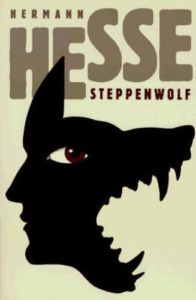

Structurally, William Burroughs’ loosely connected vignettes of sex and drugs in Naked Lunch are comparable and Isham’s prose can resemble the lengthy opium-dream passages of Thomas De Quincey. His detailed LSD trips, along with asides about classical music, are well-written but not as interesting as the politically incorrect sex and philosophy. According to Isham, in the current PC world promiscuity is only OK for homosexuals – that’s fine, he says, an advance on the days of condemning sodomites. Why though have we now become so uncomfortable about heterosexual drives? He has some homosexual encounters in this book, which may be the best defence against being labelled homophobic? Isham makes no secret that he’s influenced by Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, especially when it comes to opposing bourgeois society. All the episodes related could be called burlesques of Isham’s life – but unlike in Steppenwolf, we are unsure when we are inside the Magic Theatre or in the real world. To write this review properly I really should re-read Steppenwolf, which I haven’t thought about for twenty years.

Calling out society’s repressed attitude towards sex is Luna, a Chinese lover of Isham’s. She is wonderfully liberated, spreading her genital crabs with glee:

“LUNA. It’s my gift to you. ISHAM. An infection? LUNA. Oh, come on. They’re harmless. They’re in a – what do you call it? – symbiotic relationship with you, like the billions of bacteria already coating your penis. ISHAM. Why not ask me and try to convince me beforehand? LUNA. You wouldn’t have understood. Sometimes we have to be shown rather than told. ISHAM. What do you mean by symbiotic? LUNA. They feed off filth. They’re cleaning you. And the itching they cause is incredibly satisfying, a constant sexual stimulation. Though I admit maybe they’re more suited to women. They make me lubricate continuously.”

Luna lacks a strong voice of her own; she is too much Astarte to Isham’s Manfred. She embarks on a number of rants, one of which is about how eating food in public could be considered more disgusting than public sex:

“Couldn’t that be considered obscene in its own right and distressing in the public eye? Isn’t eating just vomiting in reverse? Why is it that we don’t consider it as such? I would say it’s because the urge to eat is just a bit stronger than the sexual urge.”

She also talks about how sugar is the most dangerous drug. These diatribes shine a light on how squeamish we are about sex and draconian about drugs far less harmful than sugar. Luna was born in Africa, and went to school there – she is a remover of the veil of illusion (that is the drab bourgeois world) like Hermine in Steppenwolf. She also arranges for Isham to have sexual pleasure with Adalat, another Chinese woman, this time an ethnic Uighur – much like Hermine introduces Harry to Maria in Steppenwolf.

However, Isham ends up raping Adalat. The rape is not violent – and the protagonist doesn’t feel guilty. If I refer to the biblically based exposition in chapter seven (Isham keeps his Bible close one notes), it may have been what he calls a ‘cooperative rape’. This was the episode in this novel, designed to disturb, which got to me. Humans do bad things, but I haven’t thrown off the idea of contrition and redemption – I like to lessen the hammer of the Christian superego but not jettison it completely. While Hesse balances his rebellion against bourgeois society with a turn towards Eastern spirituality, this is absent in Lust & Philosophy. You have to remember that Isham has seen the East, that is China, go from drab communism in 1990 to ultra-capitalism of the least spiritual kind (this book was published in 2012).

Isham, like Nietzsche, is not a big fan of guilt it would seem. He claims doing wrong to others brings them pain certainly, but it helps them develop. Forgiveness is not something he is into either:

I am philosophically opposed to the condescending rhetorical gesture known as forgiveness. My enemy is better off without it. I rather regarded her offenses against me as badges of honor earned in the struggle for mutual recognition, her failings as beautiful scars attained in the battle of life. As Nietzsche advised, learn to hate the one you love in order to ennoble this person as your proud and honest enemy – and one thus genuinely worthy of your love.

And guilt can often make people vindictive and vicious. This is exemplified by his experience in massage school in the States where he is accused of sexual misconduct:

I scour my memory for any other incidents that might have contributed to my selection as a scapegoat for the class’s surplus of sexual guilt. Nobody enters a massage school unburdened with some brand of sexual baggage. It’s what draws one to massage, just as psychologists are drawn to their profession as a way to work through their own mental issues.

Near the end there is a description of a mental breakdown, great writing about something hard to describe. I’ve tried to write something about my experience in 2014 at Beijing airport when I was in the first stages of a breakdown. All I could come up with was that in the airport everything took on a liquid aspect – when your nerves are completely out of whack even your optic nerve is affected. The next part for me was near insomnia, I could only doze because anxiety continually jolted me awake. Here is Isham’s take:

Most people at some point in their life fall under the sway of demons and feel powerless to protect themselves from internal destruction. A classic case is severe sleeplessness: the despair of being locked awake, clenched tight by another force, stripped of the ability to relax and let the body’s loving narcosis do its work. Only by the greatest mercy was I allowed to catch enough snatches of sleep to fend off escalating insanity and rapid death from the venom of full-blown insomnia.

Finally we return to the Beijing streets looking for Cookie. Lust & Philosophy has been an entertaining ride and Isham has hammered home his vision of a new free sex society:

The following operative principles are always taken for granted and can be considered laws: 1) any two people who want to have sex with each other should do so, promptly and without undue fuss; 2) where the desire is not mutual, the one with the lesser desire should consider offering sex for the sake of generosity.

Arthur Meursault (another China expat author, and obviously a fan of Camus) explains in his review of Isham’s American Rococo why this free love vision won’t work – that it won’t make people happier and how only a select few will benefit. Throwing things out and starting at year zero never seems to work well. Isham shouldn’t be the founding father of a new society – but he is the strongest voice I’ve encountered in calling out the hypocrisies and problems society currently has around sex. Which society you ask, China or America? When it comes to sex I’ve found them a bit different. In America they start experimenting as teenagers and continue to have hook-ups in their twenties and beyond, but once they are married, infidelity is a big no-no; monogamy is very highly valued. In China the young are quite chaste. However, once married and with a child or two produced, they chase then their sexual desires. It’s OK as long as it’s discreet. It usually advantages men who can visit KTVs, bars, hairdresser salons – all places full of prostitutes – or if they are rich they can set up a mistress. This doesn’t mean married Chinese women don’t have their own adventures. This is a gross generalisation of course, but it seemed to me the major difference in approach to sex when I was in China. (America here just means the ‘West’ really.) In the West you play before marriage, China after tying the knot. Not much of a conclusion to the review? A loosely structured review for a loosely structured book.

* * *

Lust & Philosophy is available from various online retailers such as Amazon.com.

An earlier edition of the book was reviewed on Bookish Asia in 2016 by Arthur Meursault.

Frank Beyer’s true crime articles have appeared in China Channel and Crime Traveller, his short stories in Fiction on the Web and travel writing in Remote Lands.