China is not usually associated with horses – well, other than being an agrarian civilisation long in opposition to the nomadic horse peoples of Central Asia – and yet it has a rich equestrian history and culture, as detailed in breadth and depth in Yin Hung Young’s The Horses of China.

The book is divided into five chapters: horses in China from ancient times to the present; art and artefacts; equestrian sports (reflecting the Hong Kong-born author’s own riding expertise); horse breeds; and traditional Chinese veterinary medicine.

Young recounts how – despite always being an importer of horses from its steppe neighbors – China was the cradle of several world-important equestrian inventions; the breast-strap harness (c. 400 BC), the horse collar (c. 100 BC) and probably the stirrup (c. AD 300). The first two inventions allowed a horse to breathe more easily and thus able to pull greater loads, and stirrups meant easier mounting and better stability in the saddle, which was especially useful in combat.

Another achievement was the “pony express” mail carrier system. I was aware of it from reading about Mongol rule of China, but hadn’t realised it dated back to the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), nor that it was so well developed by the Tang dynasty (618–907).

The system became more advanced in the Tang when a court message could be conveyed over 200 kilometres in a day. Some 1,639 postal relay stations were established across the country, and of these 1,310 were connected by horses, 260 were connected by boats and the remaining 69 used a combination of both. They were maintained at intervals of 50 kilometres along the main routes crossing the country.

Horse culture in China reached its zenith during the Tang dynasty. “The aristocrats’ great love of horses was likewise reflected in leisure and recreational activities, and was instrumental in horse dancing, polo and horseback hunting reaching an apex at this point in China’s imperial history.”

Horses were also prized during the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol rulers imposing harsh punishments for horse-related crimes. Young writes: “Robbery of horses would result in capital punishment. Anyone stealing a horse would get his nose slit or cut off. Stealing a donkey or mule would in being indelibly tattooed on the face or forehead.” In comparison, first-time offenders caught stealing sheep, goats and pigs were tattooed on the nape of the neck.

In Confucius’ time riding a chariot was one of the Six Arts; fast forward two millennium and we find government military exams, the martial version of the more celebrated civil service exams, featuring horseback archery as the first of three exam steps (the second was stationary archery and tests of strength, and the third a written exam.)

For me the weakest chapter of the book is the last one on traditional veterinary philosophy and practices. There’s too much esoteric detail for most readers, and it suffers from Young’s tendency to unsceptically repeat old folklore and popular myths; earlier in the book Marco Polo is described as “a confidant” to Kublai Khan, and modern horses breeds are traced back to the famous Ferghana (Heavenly or Blood-Sweating) horses. In the fifth chapter, we read about Sun Yang (680–610 BC) who is “credited with being the pioneer of veterinary acupuncture,” and are told about the efficacy of acupuncture for various ailments. All this simply doesn’t measure up to factual evidence; there’s no reliable proof that veterinary acupuncture was used in ancient times, nor that the modern form works.

Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, who lived in China from 1583 to 1610, was not impressed by the standard of horse husbandry.

The Chinese know little about the taming or training of horses. Those which they make use of in daily life are all geldings and consequently quiet and good tempered. They have countless horses in the service of the army, but these are so degenerate and lacking in martial spirit that they are put to rout even by the neighing of the Tartars’ steeds and so they are practically useless in battle.

It’s striking that throughout China’s history, the Chinese were unable to breed horses of sufficient quality and in sufficient numbers. In 2016 I reviewed Larry Weirather’s Fred Barton and the Warlords’ Horses of China, an excellent account of an American who set up a horse ranch in Shanxi Province, breeding the large Russian Orlov horse with the medium-sized Morgan from the United States, the off-spring of which could then be bred with the small but tough Mongol pony. The Orlovs – 3,500 in total – were secured in Siberia and driven through Manchuria and Mongolia and into China on an epic four-month trek.

What explains this constant need to bring in horses from surrounding territories? Explanations have included a lack of suitable pasture and a lack of expertise, neither very convincing – there was plenty of both in the borderlands, especially when China was under Mongol and Manchu rule.

Jasper Becker touches upon another explanation in his City of Heavenly Tranquillity: Beijing in the History of China (2008):

By a quirk of nature, the Chinese struggled to create an effective cavalry force because Chinese soil lacks selenium, a mineral essential to the breeding of sturdy horses. They could only import their mounts from the steppes, something the nomads often agreed to, safe in the knowledge that the buyer must soon come back looking for replacements. It was as if, during the twentieth century, one side always had a monopoly of tanks.

In a wide band from Tibet to China’s northeast – exactly where horses were needed – the soils lack selenium. It’s interesting speculation and a topic worth exploring.

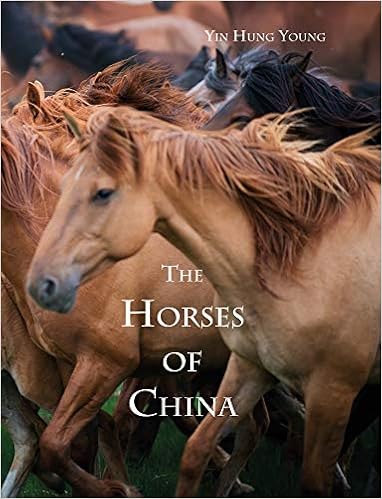

The Horses of China is gorgeously illustrated with photographs of horses and of artworks, as well as paintings and drawings. As well as good judgement in choosing images which are beautiful and informative, the author must have gone to an enormous amount of work obtaining permission from museums and other organisations.

For me, the standout image is a two-page spread of Mongol boys racing in the Naadam Festival against a backdrop of mountains. Although the landscape and horses look magnificent, it’s actually three dogs racing alongside who steal the show in their joyous tumble of legs, reminiscent of the kinetic energy in the Han dynasty-era Flying Bronze Horse of Lanzhou, one of the great artworks of world history, and pictured earlier in the book.

Among other illustrations that caught my eye was one of a PLA cavalry patrol on Hequ horses across the snow-covered Himalayas, and of various sculptures: “Ceramic dancing horse and its trainer,” and an exquisite Tang-era 18.5 cm high wine flask, “Silver saddle flash with gilded dancing horses.” On a larger scale are cavalry and chariot horses from the terracotta army buried with Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China.

And what of horses in China today? Young says the number of horses in 2019 stood at 3.7 million, a drop from 5.6 million a decade earlier. While their role in pastoralism is on the wane, rising incomes give some hope for the popularity of riding as a hobby; however, as shown by the 2008 Olympic equestrian competitions having to be held in Hong Kong rather than in China, there’s a long way to go. Young asks: “The question now is: how will China help to build the future for this steadfast animal which has served it so well, and care for its welfare?”

The Horses of China is a book with a lot of heart, written with great passion and concern for horses. It is published by Homa & Sekey Books.

For more information about the book, you can visit the author’s website: The Horses of China.