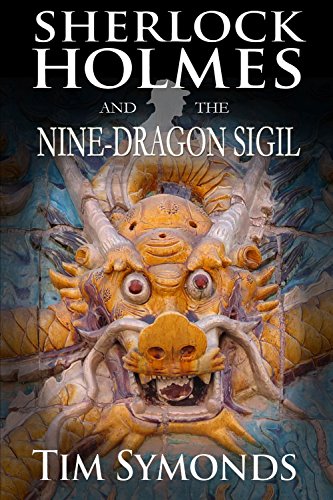

Englishman Tim Symonds is the author of five Sherlock Holmes novels, most recently the highly enjoyable Sherlock Holmes and the Nine-Dragon Sigil, which takes Holmes and Watson to the Forbidden City in Peking during the last days of the Qing dynasty.

* * *

What does the “Nine-Dragon Sigil” in the book title refer to? I had to look “sigil” up in a dictionary; was the use of this obscure word a deliberate choice to stoke curiosity?

In Sherlock Holmes And The Nine-Dragon Sigil the outdoor robe the Empress-Dowager Cixi gives to the young Emperor has a nine-dragon sigil stitched on the back. The Emperor knew exactly what this terrible message meant. I came across the word ‘sigil’ when I began extensive research on the turbulent final years of the Great Ch’ing, when the fate of the Middle Kingdom was at stake, when China could have gone in a quite different direction from the chaos the fabled Empress Dowager Cixi left behind. Although the word ‘sigil’ is used throughout the world, it was new to me too. For some months I went on pronouncing ‘sigil’ with a hard ‘g’, not the correct ‘j’ sound. Because of this I put the following at the very start of the novel: ‘Sigil. Pronounced ‘sijil’. An inscribed or painted symbol or occult sign considered to have magic power.’ A search engine has some amazing examples of sigils at www.bing.com.

What first drew you to doing a story set in China? Why did you choose the setting of Peking in 1907?

I decided on China after re-reading Holmes’s description of the countries he travelled to during his ‘Great Hiatus’. To avoid death at the hands of a vengeful Colonel Sebastian Moran and other remnants of the deceased Professor Moriarty’s gang he went walk-about for three years. In ‘The Adventure Of The Empty House’, Holmes related, ‘… the trial of the Moriarty gang left two of its most dangerous members, my own most vindictive enemies, at liberty. I travelled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhassa and spending some days with the head Lama.’ I thought, if Holmes got as far as Tibet, he might have developed an ambition one day to follow in the steps of Marco Polo all the way to Cathay. Polo’s journey needs investigation. As I pointed out in my novel ‘Sherlock Holmes And The Dead Boer At Scotney Castle’, if Polo really did get to the heart of Imperial China why did he never mention the Great Wall? Why did he never mention the practice of binding infant girls’ feet?

Why 1907? All five of my Sherlock Holmes novels are set in the Edwardian period. Those ten years when King Edward VII was on the throne of England saw the beginning of the end for the immense European empires. They were when Holmes and Watson left 221B, Baker Street and came back together almost on a hit-and-run basis, held together through comradeship forged in the late years of the Great Queen Victoria, yet in many respects warmer.

What are the challenges of taking Sherlock and Holmes out of Britain and placing them in an exotic setting? For example, how do you handle the communication barrier? Do you just cheat a bit and have all the major characters speak passable English?

In short, yes, I have foreigners speaking competent English. In ‘The Nine-Dragon Sigil’ the young Mandarin acting as a guide speaks excellent English. Many of the text books he would almost certainly study would be in English and clearly he was happy to practice spoken English with Watson in particular. Sometimes I drum up a local interpreter to ease the dynamic pair’s path, but luckily by the early 1900s the English language had found its way to the most remote corners of the world as well as both poles. This was partly due to the extraordinary spread of British and American explorers and missionaries from Victorian times onward (‘Dr. Livingstone, I presume?’), further enhanced by the spread of British and American traders and entrepreneurs, and by the magnitude of British and American fleets, both merchant and military, and the administration of the British Empire covering a fifth of the world’s landmass.

Both The Sword of Osman and The Nine-Dragon Sigil take place against a backdrop of waning empires. Mere coincidence or is it related perhaps to having been born at the tail-end of the British Empire, which predisposes a chap to this fading grandeur?

That’s correct. To people with an historical bent, the time I place Holmes and Watson in (that long-gone Edwardian era) was a period when the world was accelerating towards the terrible First World War. Watson certainly sensed this but was sure ‘England’ would defeat the upstart Kaiser’s Germany in months. Looking back we can discern corrosive economic and political processes at work though even decades later Great Britain still controlled the largest Empire by land-mass and population ever to have existed. In fact my first job was as a youthful Assistant Manager on a large sheep farm in the Kenya ‘White Highlands’ at the very end of Colonial rule. Not incidentally, I have in mind a further Sherlock Holmes centred on the last days of the Romanovs, thereby continuing Holmes’s intrusion into the final days of once-great empires and dynasties.

Is coming up with clever mystery elements the most difficult aspect of writing Sherlock novels?

It sure is. And it presents a heck of a problem – who exactly is my readership? If the mystery is solved easily, won’t I lose the more serious reader of detective fiction, the one I hope I’m writing for? On the other hand, if I make the reader work just as hard as Holmes and Watson, will some fall by the wayside? Must every novel end where Holmes’s miraculously snatches the solution out of the air, or will the Great Detective once in a while falter and fall short, for example confronted by the unbelievable complexity of life in the Forbidden City? In ‘The Nine-Dragon Sigil’ I soon realised it was impossible for an outsider to fathom what was really going on. As a result, Holmes came within a hair’s breadth of complete failure. It was only his knowledge of Hamlet that helped him carry the day.

Sherlock Holmes And The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter is the best-selling of your novels. Can you tell us something about the story?

As you say, ‘The Mystery of Einstein’s Daughter’ is selling well and one reviewer ascribed this to the fact both Einstein and Holmes are world-famous names, the one real, the other fictional but considered real by millions. I had great fun researching ‘Einstein’s Daughter’ not least because I wish I had taken more Physics at school, though I did take Physics 10 at UCLA while working on a degree in Political Science. ‘Einstein’s Daughter’ is based on a real mystery in Albert Einstein’s life that has never been solved. I wrote in the preface: ‘Even today it is not widely known that at the age of twenty-three Einstein’s ambition (to become a physicist greater than Isaac Newton) was threatened when he sired an illegitimate daughter with Mileva Marić, a physics student he met at the Zurich Polytechnikum, later his first wife. Mileva and Albert referred to the infant daughter by the Swabian diminutive ‘Lieserl’ – Little Liese. Her life was fleeting. At around 21 months of age she disappeared from the face of the Earth. The real Lieserl may never have come to the attention of the outside world but for an unexpected find eighty-three years after her disappearance.’

What first inspired you to write? Was writing in the blood? I’ve read that prolific English novelist Elleston Trevor (Flight Of The Phoenix and The Quiller Memorandum) was an uncle.

The first inkling I might one day transmogrify into an author was during my boarding school days in the Channel Island of Guernsey, at Elizabeth College. After the prefects signalled ‘lights out’ I would regale the other little tykes in the ‘Long Dormitory’ in the central turret with made-up stories. Certainly an uncle, Elleston Trevor, also in St. Peter Port, must have had an influence though for his first few years as a would-be author he had a very difficult time. He was so hard up that during my summer holidays at home he used to flick pebbles up at my bedroom window at six in the morning to get me to creep downstairs and make him breakfast in a small unused kitchen at the back of the house so my mother wouldn’t know. I don’t believe anyone in my family thought he would ever make it as an author. How wrong they were. Even I am astonished at how well his reputation has held up, long after he has gone to the Writing Room in the Sky after a very contented long last period in his home in the mountains of New Mexico, near where ‘Flight of the Phoenix’ (clever title) was shot.

The life-style of an author before becoming well-known is as tough as it gets. However, once you become better-known and can survive financially it’s the nearest thing to paradise. You choose what hours or days to work, you spend time researching wonderful topics, you live where you want to live, in English woodland as I do, or overlooking beaches in the Caribbean, or in a hill-top house in Sri Lanka.

Above: Where it may all have begun, Tim Symonds’ Prep school. That central tower was where the Long Dorm was sited.

What are your writing habits?

First, I go through weeks, even months, of active displacement, turning on the computer but doing everything else rather than getting started on the new novel. Sometimes I go 200 metres along a farm track from my home (a converted oast house) to the tea-room at Rudyard Kipling’s old ironmaster’s house, Bateman’s, and wander around this National Trust property, puzzling how to start. Often I go out into the nearby woods and try to work out what plot to come up with. Suddenly ‘Peking’ pops into my mind. That led to ‘the Nine-Dragon Sigil’. Six years ago ‘Sofia’ popped into my mind. That led to ‘Sherlock Holmes And the Case of the Bulgarian Codex’. Three years ago ‘Stamboul’ (Constantinople) popped into my mind, and that led to ‘Sherlock Holmes And The Sword of Osman’. I begin ordering books. I go online for further research. I email people around the world with expertise I could use in the plot, sometimes they’re other authors, professors, scientists, historians. I go out for walks with a small note-book and pen. On my return I transcribe on to ‘Notes’ whatever I’ve scribbled down. Gradually the notes grow to 80 pages or more, containing hundreds of items, perhaps 15,000 words. From these pages, like the early universe minutes after the Big Bang, clumps begin to form which might become chapters. I start to arrange them in sequence and work on them like an architect on a blueprint. 6 or 8 months go by while all this is taking place. The process becomes very complex and I begin to feel like a juggler.

And, finally, I come to the best part, the fine-tuning. This is a really important stage. One example comes immediately to mind. I thought I had completed ‘The Nine-Dragon Sigil’ and was about to send it to MX Publishing but a niggling thought entered my head. Hadn’t I given the young Emperor a rather wimpish part? It’s true he was brow-beaten by the Empress Dowager, frightened silly of General Yuan and Chief Eunuch Li but was he completely bereft of fight? By composing a twist in just a couple of paragraphs I gave myself and the reader a quite different view of him. If his own devious plot had not been thwarted, the whole history of China could have been different.

Above: Tim Symonds’ favourite ‘writing studios’ tucked away in deep woodland in the Sussex High Weald. It’s where he wrote most of ‘Sherlock Holmes And The Nine-Dragon Sigil’.

One of the facets of writing I like best is the intensive background reading it requires. It’s obvious reading your novels that you also love doing research. What were some of the books you read for The Nine-Dragon Sigil?

I must have read thirty or more books on Cathay as the Great Ch’ing tottered to its grisly end, selecting always the ones which told me what life was like in the High Court and the Forbidden City at the time. A full list can be found in the references at the end of ‘The Nine-Dragon Sigil’. I especially recall the following:

‘The Opium War’ by Julia Lovell.

‘The Dragon Lady’ by Sterling Seagrave.

‘Empress Dowager Cixi’, by Jung Chang.

‘Yuan Shih-K’ai’ by Jerome Ch’en.

‘A Mosaic Of A Hundred Days’ by Luke S.K Kwong.

‘With The Empress Dowager Of China’ by Katherine A. Carl.

‘The Scramble For China’ by Robert Bickers.

‘Two Years In The Forbidden City’ by Princess Der Ling. The recollections of someone who became the Empress Dowager’s favourite in Court.

‘Opera And The City’ by Andrea S. Goldman, a specialist insight into the politics and culture of Peking from the late 18th Century to 1900.

And finally, a good yarn though not always strictly truthful, J.O.P. Bland & Edmund Backhouse’s ‘China Under The Empress Dowager’. Sometimes fanciful but fun.

What are your favourite film, television, and radio productions of Sherlock Holmes stories?

I’m very keen to see my own novels turned into a short season of television plays, in the case of ‘The Nine-Dragon Sigil’ possibly for the vast Chinese market so I have kept an eye on repeats of old series on British television. My favourite Holmes portrayals are by Peter Cushing, Basil Rathbone, and especially Jeremy Brett. All portrayed Holmes and Watson as I believe Arthur Conan Doyle meant them to be. Now Jeremy Brett has gone, who now?

If you could dine with any literary figures past or present, which ones would make your short list?

From when I left school at 16, until I was about 40 years old, I lived a life of great adventure, first Africa, ‘the Dark Continent’, then Latin America, especially Mexico, then California (mostly UCLA) and the Caribbean (especially Jamaica). During my travels I read Hemingway’s stories. I’d have given a lot to meet up with him when he was on safari in Kenya and Tanganyika.

As to a living author, I’d like to have lunch with Jung Chang who wrote ‘Empress Dowager Cixi’ as well as ‘Wild Swans’, ‘Three Daughters of China’ etc. She writes, ‘I have had the good fortune to utilize a colossal documentary pool, as well as consulting the First Historical Archives of China, the main keeper of the records to do with Empress Dowager Cixi, which holds twelve million documents’. Good grief! What she learnt in writing these exceptional descriptions of the Empress Dowager and life in China under her rule would make for gripping conversation.

What projects are you working on now?

The five Sherlock Holmes novels I’ve written all have subterranean rumbles of the imminent catastrophe of the Great War of 1914-18. I’m now tempted to try my hand at a television series set in the English county of Wiltshire (of Avebury Ring and Stonehenge fame) in 1916. The six upper-class girls at the core of the story are doing their bit for the war effort by training horses and mules imported from America for duty on the Western Front. Of course there’ll be enemy Zeppelins dropping incendiaries and high explosives, a spy hidden among the grooms, ups and downs in the girls’ lives, and a nostalgic end when the Armistice is announced in 1918 and they know they have to separate and find their way out into the complex, changed world just ahead.

Links: Tim Symonds’ books are available from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and various other retailers. They are published by MX Publishing.

Read my Bookish Asia review of Sherlock Holmes and the Nine-Dragon Sigil.