“No poetry or memoirs,” warn some publishers in their submission guidelines. To be paired with poetry – yes, cruel, but the truth is often cruel. The fact is that the general reading public is not interested in non-celebrity memoirs, and the number of sales (or copies given away) is usually proportional to the number of family members.

There are exceptions, memoirs that are beautifully written and those that cover eventful times. On that last count, Witness to History qualifies in spades. As the author himself says in a chapter titled “America the Beautiful, 1958–1998”: “It took sixteen chapters to tell about the first thirty-eight years of my life while the next forty will take only one. The disparity speaks for itself as to the turmoil of the first thirty-eight years.”

Among those tumultuous decades, Hoffmann writes that three particularly bad times stood out:

The six months under Hitler undoubtedly was the worst time. It is hard to say which was worse when comparing the other two episodes: life in the Hongkew Ghetto or life under the Communist Regime from 1949-1952. Each one was horrible and difficult for different reasons.

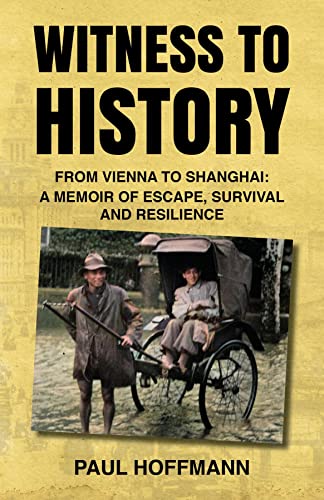

Born and raised in Vienna, Hoffmann was the son of a doctor. With the annexation of Austria in 1938, life became perilous for Jews such as the Hoffmanns, and escape plans were put into action. Paul headed to Shanghai, an open port not requiring an entry visa. After various difficulties in getting permission and finding a vessel, and a four-week voyage, he arrived in Shanghai on November 28, 1938.

The arrival in a new world was unforgettable – the “commotion, noise, strange people and an indecipherable language” but made smoother by the local Jewish Refugee Committee, who took him and fellow refugees to their accommodation (low-end abodes of the bucket-for-a-toilet variety) and the help of distant relatives.

The 18-year-old soon found his feet, making a living from tutoring, and was able to bring his parents and sisters over. Life became harder in 1942 when European Jews who had arrived after December 31, 1937 were squeezed into the “Jewish Ghetto” in the Hongkew district, though the Hoffmanns were able to delay their move until the following year.

The author’s recollections do not linger on the suffering endured; this memoir is not misery porn. Of the erratic, cruel Japanese officer in charge of the district police station, “I could tell many stories about this horrid little man, who had the audacity to call himself the “King of the Jews” as he swaggered around the Ghetto, but I prefer to go on.” Hoffman’s narrative concentrates on difficulties overcome and life going on despite everything.

The Ghetto became a little city unto itself with its own newspapers, health facilities, stores, tradesmen and entertainment. This economic and social development was made possible, in part, by funds coming in from the United States through Switzerland to support those that could not support themselves. The Chinese people in the area participated in the economy, people like me brought money in from outside the Ghetto and many people sold what they had left, including jewelry, even wedding rings. I sold my stamp collection when things got tight.

Despite suffering under Japanese occupation, Hoffmann has praise for the discipline of the troops during the power vacuum between the sudden Japanese surrender and the arrival of Chinese and Allied troops:

The end of the war brought incredible feelings of elation and hope. These feelings were tempered at first by the fear of potential retribution by the Japanese Army, or a Chinese mob that might engage in looting and all the other terrible things mobs might do. This did not happen, primarily due to the amazing discipline of the Japanese military.

The Japanese were told to keep order and they did. The Japanese soldiers were subjected to all kinds of physical attacks from those they had oppressed. The Japanese sentries were spat upon and rolled along the pavement. They did not retaliate.

Whereas most Jews in Shanghai were keen to leave – they resettled mostly in North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel – Hoffmann stayed on after the war (and also after the Communist victory in 1949). He had his Law studies and work, and life was good for those like him who were getting paid in U.S. dollars.

Hoffmann earned a law degree in the summer of 1946, an amazing achievement given he was also working to support his family during those years. At that time, Western businesses were moving back into Shanghai, and among them was Allman, Kops, and Lee. This was a law firm, founded by Judge Norwood Allman, (1893–1987) a legendary Old China hand who was a lawyer, businessman, diplomat, newspaperman, and America’s China spymaster. Hoffmann describes Allman as not only an important influence on his life, but one of the most interesting people he ever met. He was a man of “exceptional integrity and courage … generous to a fault with his friends, an excellent horseman and a hard drinker, an important quality in foreign outposts.”

Allman’s account of his time in China, Shanghai Lawyer (1943), is one of my favorite China books. (I reviewed it on Bookish Asia a few years ago after Earnshaw Books reissued it with some additional material.)

Looking back at his Shanghai years, Hoffmann expresses gratitude for his good fortune and takes pride in his achievements:

Here I was, just twenty six years old, with a good job at an American law firm and teaching once a week at a French Jesuit university. All this happened just eight years after I had to leave Vienna as a refugee, with ten dollars in my pocket, having survived extremely difficult living conditions, including serious illness. To this day, I sometimes have difficulty grasping how I managed to accomplish this under such challenging circumstances.

Hoffmann’s law work wasn’t only lucrative but interesting and varied, with clients from local businesses to international giants like General Electric, Coca-Cola and Kodak, to individuals of note. “I met General Douglas MacArthur’s nephew, who wanted a divorce, witnessed the will of General Claire Chennault, commander of the Flying Tigers, and met many other interesting and well-known people.”

Nineteen fifty was an eventful year for Hoffmann: he married Shirley, a Russian Jew, the Korean War began, which, by placing the U.S. and the PRC in conflict, made things impossible for Allman. He departed, leaving Hoffman in charge of the law firm, or at least in charge of closing it down. This was not easy because moving funds into China became problematic.

Judge Allman left early in October 1950, and at the age of thirty I found myself in charge of a law firm, a branch of a major shipping company, various other smaller businesses and the Allman household, including their five servants. At least seventy people looked to me for their paychecks.

Hoffmann left Shanghai in February 1952 for the United States by way of Europe. He had a successful career in corporate law, most of which was with General Electric. After retiring in 1986, he began writing his memoir, which he completed a dozen years later. Paul and Shirley Hoffmann returned to China for a visit in the spring of 1998. Paul Hoffmann passed away in 2010 at the age of 89; his wife Shirley followed him two years later at age of 84.

Originally intended as a history for the family, the memoir, his daughter thought, was of value to a wider audience, and she took on the project of editing her father’s text, adding photographs and various documents. I have sympathy for the hassles she had dealing with no longer compatible word processor discs. She was introduced to Earnshaw Books by Liliane Willens, whose memoir of Jewish Russian life in Stateless in Shanghai, was published by Earnshaw Books in 2010.

Witness to History is written in a conversational matter-of-fact way that engages and rings true. The relative plainness of the prose is a virtue, letting the relentless historical twists and turns do the heavy lifting. Witness to History steers well clear of some pet peeves I have with memoirs: it’s not written as therapy (some books literally start life as therapy homework, as in “My therapist told me to write down…”); it doesn’t have the overwriting and excess introspection that comes from attendance at a creative writing course; and it doesn’t pretend to give a 20/20 vision of the past, with all the gaps filled in, and dialogues recreated for an immersive but ultimately untrustworthy account – Hoffmann, in contrast, peppers his story with the limits of memory, “I don’t recall,” “I don’t remember,” and so on.

Earnshaw Books is to be commended for its steady output of memoirs. As I mentioned earlier, many publishers won’t even look at them. In this case, though, I think it was an easy decision to take on the book. It is a compelling tale, and while it covers well-trodden ground in Austria and wartime Shanghai, the sections on post-war and particularly post-1949 life in the city make it a valuable addition to the literature.

Witness to History is published by Earnshaw Books.

A recent episode of the excellent Barbarians at the Gate podcast features hosts Jeremiah Jenne and David Moser talking with Jean Hoffmann Lewanda about her dad and the book.