Laid low by a mystery ailment and sleepless nights, I was struggling to get through my to-do list, top of which this sat Larry Feign’s pirate saga The Flower Boat Girl. Oh well, if Robert Louis Stevenson could write Treasure Island while bedridden, then I could at least read and review a book; and an immersive voyage to distant lands, lives and times could be a soothing distraction.

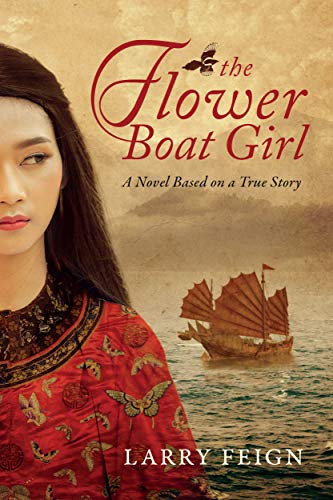

Whereas RLS’s foundational novel was a girl-free tree house – manly adventures written for boys – The Flower Boat Girl tells the story of a remarkable real-life woman, Shek Yang (1775–1844) who rose from poverty to pirate royalty in southern China in the early 1800s.

In this fictionalised account, Shek Yang’s mother dies in childbirth, leaving the seven-year-old alone with her father, from whom she learns the skills he would have taught his dead son.

He taught me to fish. How to read water. How to properly dry nets, coating them with egg whites when there was money to spare—if he hadn’t exchanged it yet for wine, if he hadn’t gambled it into the air.

He taught me to read the weather: a crow’s cawing meant fierce wind and rain, a goose feather on the water meant an approaching storm. Always bad.

The father’s gambling debts lead him to sell Shek Yang into prostitution at the age of thirteen. She serves on floating brothels, euphemistically called “flower boats,” until she is twenty-six.

It took thirteen years—half my life—before they informed me I’d paid off my debt. My father’s debt.

They invited me to stay. They implored me. I was one of the best, they said: beautiful, artful, voluptuous, and poised.

She is not free for long, however, being captured in a raid by a local pirate chief, Cheng Yat, who is struck by her beauty, but also her tooth-and claw feistiness. When the taciturn pirate expresses admiration for her spirit, she is moved:

My ears tasted the words they’d received, the way a tongue stirs a delicious morsel held in one’s mouth. As brutish and despicable as this pirate chief was, as criminal and ugly and mean, no man—none of the tens of thousands who had entered my body and moaned in my face—not a single one had ever uttered such words. I’d heard my beauty lauded, bed skills praised, my breasts and hair and teeth extolled. But no man had ever before praised my spirit.

They marry, and she gets a new name, Cheng Yat Sou. Life goes on – two steps forward, one step back – as she learns to accept her husband and circumstances, reluctantly becomes a mother, displays a genius for tactics and strategy, confronts resistance from dismissive male rivals, and masterminds her husband’s rise to power, culminating in a confederation of pirate bands known as the Red Flag Fleet.

This is a highly immersive novel, which in part comes from it not having Western characters. There’s no East meets West clash of characters. Only one Westerner appears, and it’s a brief cameo in the form of a ransomed prisoner they call Tah-nah.

Cheng Yat nudged the red-haired one with his foot. “You. From where? What cargo?”

The foreigner reared back and spat out a word which sounded like a Cantonese good luck blessing. But the growl in his voice and his hateful glare implied that his language held an entirely different meaning for the word fook.

We’re so used to Western characters getting the juiciest roles, that on encountering Tah-nah, I half-expected him to become a valuable crew member and love interest for the protagonist. Nothing doing. His role remains minor and unflattering; the belligerent foul-mouthed redhead moves off-stage and is eventually ransomed off and plays no further part.

On Feign’s website for the novel, he explains that the episode of the captured British sailor comes from real life. The man was John Turner, first mate of a trading vessel on its way to Macau, who spent six long months as a guest of the commander of the Red Flag Fleet. As ransom negotiations dragged on, he was witness to his potential fate: Feign writes on his website:

Turner had good reason to believe the gruesome death part. A day or so after sending the letter, two Chinese captives were nailed to the deck through their feet and viciously tortured before their “death by a thousand cuts”, a method of slow execution too barbaric to describe here were at a stalemate.

The novel feels authentic in the details of piracy: no treasure chests in sight, not even hauls of exotic cargo like porcelain, silk, and spices. Instead, our pirates go after once-valuable commodities such as salt. The shifting political environment of the South China coast is also portrayed well: the fragile pirate alliances, alternating government crackdowns and laxity, government pardons and recruitment. And despite its driving forward momentum and suspense, the storyline doesn’t feel forced – major events sometimes just happen, without reason or forewarning, as in life.

The Flower Boat Girl is well written though the narration is overall a little plain for my tastes, and I was not often struck by phrasing I wanted to steal; however, readers will have different thoughts about whether that is a good thing, one school believing that the writing should not distract from the tale, the other preferring wordplay. Which camp I lean towards is perhaps revealed by the last tale of piracy that I read, the guilty pleasure of Jeffrey Farnol’s purple prose in Black Bartelmy’s Treasure, which opens with English prisoner Martin Conisby shackled to the oar upon a Spanish galleon, skin “burnt nigh black by fierce suns … scarred by the lash”… “as I strove at the heavy oar I prayed ‘twixt gnashing teeth a prayer I had often prayed, and the matter of my praying was thus: ‘O God of Justice, for the agony I needs must now endure, for the bloody stripes and bitter anguish give to me vengeance – vengeance, O God, on mine enemy!’”

Memorable phrasing in Feign’s novel include the colorful local colloquialisms and cursing:

“What the prick-eating devil is he doing?” He shot into the air and screamed. “The mother-buggering turtles!”

Feign favors Cantonese over Mandarin, and we learn some fun expressions; context gives meaning but they’re also explained in a glossary. Examples include:

talk-three-talk-four 講三講四: Chit-chat or gossip

ji-ji-ja-ja 吱吱喳喳: Gibberish

There’s a lovely passage where Chek Yang is bonding with the wife of her brother-in-law. Her new friend is complaining about the menfolk’s egotistical pride in having high-sounding titles (“mouth-farting honorifics”) bestowed by Peking for their fight against rebels in Annam, when the topic turns to titles used in the world of flower boats.

“We had ornamental titles too,” I said with a little smile.

Chat’s wife blinked, still too embarrassed to speak.

“On my last flower boat they made me call myself Precious Hairpin.”

Chat’s wife bit her lips. I could see she wanted to laugh.

“Better than the name I started with on the previous boat. Are you ready? Purple Cuckoo.”

“Her laughter exploded in my face while I ran through my other aliases over the years—Black Jade, Laughing Plum Blossom, and my favorite, Fragrant Peach.

“I want a title too! Give me one,” she said.

The book moves along at a decent clip yet from the turn of events – far into the story and she’s still a wife without direct power – we guess correctly that the novel is set up for a sequel. Indeed, it ends with her ascendance to leadership of the pirate band.

The Flower Boat Girl is an enjoyable and immersive read, successfully transporting readers to a shadowy maritime world two centuries ago. Drawing authenticity from being based on real people and places, the novel also benefits from the author having a free hand due to the paucity of known facts about Shek Yang and filling in the gaps with style. A lot of work and thought have gone into the book, not just in the research and writing but in the balance achieved with so many competing elements: gritty realism without dwelling on sordidness and horror, historical information without it being homework, and having engaging characters who are not too modern.

The Flower Boat Girl is published by Top Floor Books.

For more information about the novel you can visit the book website.

You may also be interested in reading my Bookish Asia review of Larry Feign’s AIEEYAAA! Learn Chinese the Hard Way: The English-Chinese Cartoon Dictionary.