What’s the laziest way of writing a book? Throw together your blog posts or diary entries? No, that still requires you to have written something. An anthology? And one from a writer’s group or “colony.” Fiction or non-fiction, no problem, and let the laziest artists submit poems: “I’m still working on my epic China novel, but in the meantime here’s my free-form haiku.” Yes, some of the pieces will be pretty bad – the “writing as therapy” members are sure to submit recently remembered childhood trauma episodes – but they can be sold as adding diversity.

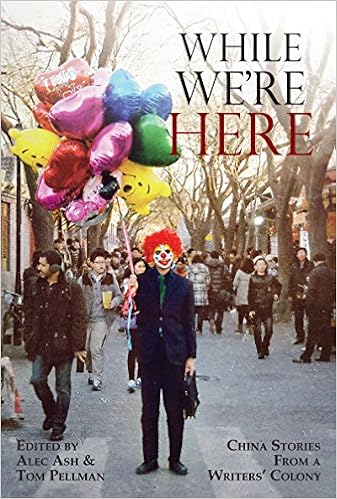

While We’re Here is an anthology of thirty-three works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry from a writers’ colony based in Beijing. But don’t worry – it’s well worth reading. Putting an anthology together is actually an enormous amount of work, and editors Alec Ash and Tom Pellman have done an excellent job finding quality contributions. They set out determined to avoid the clichéd “bizarro” stories and standard news frames on China, and they’ve succeeded.

The title While We’re Here is a statement on the transience of foreigners in China, and one that applies to the anthology writers as almost a third of them no longer live there. Though the stories don’t really address why this should be so, they do tackle questions of identity and integration, and the degree to which outsiders can fit in.

The book’s origins lie in a Beijing writers’ collective called the Anthill, the name inspired by a new Chinese expression yizu (ant tribe), which describes struggling young college graduates, unemployed or underemployed despite their industriousness and often living in cramped anthill-style conditions. As well as having an online presence, the Anthill organizes storytelling events in Beijing. Previous get-togethers, “Writers and Rum” and “Scotch and Stories,” suggest a dark interest in the alchemy of alcoholic alliteration.

Although the While We’re Here pieces steer clear of overtly political topics – reasonably so given the aim of not rehashing news and blog tropes, the Cultural Revolution casts a shadow in some of the stories. Karoline Kan’s Examining the Past recounts how resentment of her father’s indifference to the family softened as she learnt about how his youthful promise and dreams had been repeatedly crushed.

For me, the clear standout chapter is David Moser’s The Book of Changes, which describes the American’s involvement with the local jazz scene over the past quarter century. I don’t care for jazz, but through this subject we get insights into politics, culture, and modern history.

One striking characteristic of Chinese jazz musicians was their uniform reverence for Miles Davis. Almost to a person they preferred the spare, cooler style of Miles to the rapid pyrotechnic displays of other jazz artists. They pointed to his use of empty space and understatement, “saying more with less”, all preferences that, it seemed to me, had a resonance with Chinese visual arts. The best selling jazz album of all time is Miles’s classic Kind of Blue. In the liner notes to the album, pianist Bill Evans compared jazz improvisation to the art of calligraphy. I remember at the time thinking that it was a gratuitous comparison, a trendy invoking of Oriental exoticism. But it turned out my Chinese musician friends also saw commonalities in the two disciplines. The calligrapher, like the jazz artist, spends a lifetime mastering the basic forms in preparation for a spontaneous moment of creation, during which the artist must act in a non-deliberative way to produce one continuous, expressive “line” – for the calligrapher in space, for the jazz player in time – without the option of revising, restarting or rethinking. Each time the result is a unique form reflecting the artist’s mental and emotional state at that moment. Miles’s philosophy of jazz seemed to echo centuries of Chinese aesthetics. He famously told his sidemen, “Don’t play what’s there, play what’s not there.” If that’s not Daoism, what is?

Another favourite is Laszlo Montgomery’s Made in China. As a regular listener to Montgomery’s China History Podcast, and used to his sunny Californian optimism – the man is good-natured to a fault – I found his cutting remarks on Chinese manufacturing and Western importers especially powerful. Since 1989 Montgomery has been helping Chinese manufacturers deal with foreign buyers and companies. In Made in China he laments the decline of the old system of building relationships. The Internet changed everything:

All of a sudden, it was simple to slam that China price down to the bone marrow. All you had to do was find six to eight factories, ask them to quote your sample, and go with the lowest cost producer. If the factory you preferred wasn’t the cheapest, you took the lowest price and waved it at your top choice, offering them a last chance. If the first choice factory didn’t take the order, number two or three did. The prevailing thought on the Chinese factory end was that this money-losing order would open the door to future profitable opportunities. The Great Lie.

While American consumers have benefited from low prices, the factories have seen their profits squeezed to razor-thin margins: “The supply chain from China to US distribution centers has now been tightened down to levels undreamed of thirty years ago.”

Montgomery also explains that the blame for the shoddiness of Chinese goods lies with the foreign retailers insisting on the very cheapest materials and designs.

All the poorly made schlock that you put in your shopping basket at your local dollar store was signed off on by a buyer back home. If they said this piece of shit was good enough for the American consumer, the Chinese factory was happy to comply. Imagine how I felt sitting on the Chinese side of the table when some American retailer, for the sake of hitting a price point, gave the factory the thumbs up on a flimsier, cheaper material.

Both of the chapters I’ve quoted from were written by old-timers, which is unrepresentative of the anthology because the bulk of contributors are young, more recent arrivals. There isn’t space to mention all the chapters I enjoyed, but Aaron Fox-Lerner’s Back and Forth: A Short Story impressed, as did Sascha Matuszak’s Flower Town: Rise and Fall of a Sichuan Village. Sam Duncan’s account of his year in the northeast city of Daqing, Ayi and I – An Unexpected Friendship, perhaps best encapsulates the China experience for many expats. Duncan arrives in Daqing, “employed by an ‘educational consultancy’ firm to work as a foreign English teacher for a year in a local primary and middle school – basically a money-making scam.” He’s promised an “absolutely fabulous” apartment, but when he opens the door:

I soon realized it was the worst place I would ever spend a night in, let alone live in for a year. My apartment looked like it had been decorated by a deranged North Korean interior designer, with peach-colored plastic over the walls, industrially bright spotlights, dying plants in random corners and hundreds of children’s stickers plastered everywhere. There was no hot water. The TV may well have cost a lot of money new, but it was 15 years old and broken. The kitchen was covered in grease and dirt. The bathroom was caked in mildew, mold, rust and dust. The single bed had a bare black-mold infested mattress on it that might have outdated the TV. The only decoration was a candle stuck in an empty Tsingtao beer bottle.

He’s rescued by an elderly female neighbor with whom he develops an unlikely friendship:

Even in top-tier Chinese cities it can be hard to find older people who see past your foreignness and treat you like a human being. As we saw more of each other I felt grateful that she didn’t pepper our chats with empty praise of my Chinese, my chopstick skills, or my ability to eat spicy food without choking to death. It was mostly because of her and her family’s kindness that I decided to stay in the flat. She told me to call her Ayi – Auntie – and although she later told me her real name, I never used it and promptly forgot it.

While We’re Here observes the first rule of contemporary China writing in having a reference to Peter Hessler, the patron saint of the English-teacher-would-be-bestselling author. The Hessler mention is in Alec Ash’s funny and descriptive In the Hutong. Hutongs are the alleyways of the traditional residential areas of Beijing, and living in them seems to be de rigueur for any aspiring China writer:

I have friends who can stake a much better claim to their hutong than I – who have pigeon aviaries on their roof, or a blocked-off escape tunnel in their basement. Tom Pellman, my co-editor on this anthology, has lived in Ju’er Hutong, one block west of me, for six years. It’s the same hutong Peter Hessler lived in and wrote about (we’re both fanboys), and long before him Edmund Backhouse wasn’t far away (ditto).

Fanboys of Hessler – fair enough – but I hope he’s joking about Backhouse. Edmund Backhouse was one the great expat eccentrics of old Peking, a brilliant linguist but he was also a swindler and a sexual degenerate.

While We’re Here showcases an abundance of young talent that we’re going to hear from in the future. Some of the writers, including Alec Ash and Robert Foyle Hunwick, already have contracts with major publishers.

This anthology, currently available only as an ebook, is published by Earnshaw Books. It is also available on Amazon.