Any expat in Asia grumbling about the stifling summer heat, oversized bugs, or the difficulty of tracking down decent cream cheese, would do well to read Rosie Milne’s superb Olivia & Sophia. Although at its heart a love story describing the marriages between British colonial official Sir Thomas Stanford Raffles and his two wives, such are the hardships of travel and isolation, the threats of disease and death, that it leaves you feeling relieved to be living now rather than in the early 1800s. I read Olivia & Sophia while suffering from pneumonia, and in my weakened state, I felt so grateful for the modern blessings of medicine, air-conditioning, refrigeration, and reliable brewing technologies, that I got through the entire book without my usual lament of having missed all the fun of annexing territories and ruling natives.

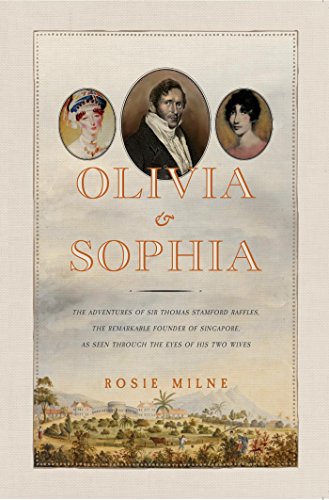

The story is told through the diaries of Raffles’ two wives: Olivia Mariamne Devenish and Sophia Hull. Olivia is the wild beauty – strong-willed and flirtatious; Sophia is the more respectable wife – pious and educated, plain but steadfast.

Both diaries take us from domestic concerns in England to the sultry ports and steamy jungles of Southeast Asia. Of course, just getting there is an adventure in itself, and the arduous voyage out is very well described. Olivia writes:

Worse even than our cabin’s lack of light is the lack of fresh air. Already I feel half-poisoned by a variety of stinks: the chamber pot effluvia and vomit from seasick passengers; the drifting smells of that detestable tar the sailors use; the emanations from that odious galley, which I suspect will produce only ill-concocted soups, queer-looking ragouts, and jellies the colour of saltwater.

Then again there is the stink of the animals. The fore lower deck is as usual a crowded manger: sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits, and a cow are all in pens, shuffling and bleating in hay already malodorous.

On top of the voyage’s physical discomforts are the long months of claustrophobic social tensions and intrigues. Olivia is older than “Tom” and comes with a past which she fears will taint her husband’s prospects. Indeed, on the voyage out, it soon becomes clear that her secrets – chief among them an illegitimate daughter called Harriet – have become shipboard gossip, and she is shunned by the other female passengers.

’Twas clear as gin one sister had whispered to the other the scandal she’d had from her husband – I mean I knew at once Mrs. D had whispered to Miss. W about Jack and Harriet. What’s more, they knew that I knew that they knew. All this was clear from the telling glances we now exchanged – theirs glittery as icicles. Nothing was said, of course; these were well-bred ladies that knew they must say nothing of my past.

The cold reception from the Western ladies continues in their first posting of George Town, Penang, but it doesn’t trouble Olivia too greatly as she’s happy to interact with the locals. It’s an example of her – and her husband’s – progressive views; they’re both polite to servants, tolerant of native ways, not too religious, and are fully behind the drive to end slavery. Is this the author pandering to modern sensibilities? It’s natural to want characters with similar moral compasses to our own. Indeed, we want to imagine that had we been born earlier we’d be on the right side of history, too. This, of course, is part conceit, part wishful thinking – and it’s impossible to know. Instead of manning the barricades in defence of egalitarianism, we’re just as likely to have been caning servants for having spilt our drinks. As for Olivia & Sophia, yes, there’s been a little concession to present-day attitudes but not unduly so; Milne was lucky with her characters – the historical record shows they were enlightened on a whole range of issues.

The novel is a fictionalised account so there are embellishments; for example, Milne has the wives accompany Raffles on some trips when in fact they actually would have stayed at home. However, the source material is so rich with drama – too much drama in the form of deaths – that some of the true story needed to be toned down. The author explained in a Bookish Asia interview that it was necessary to lessen the body count: “otherwise I’d have had a death on every page, which would have been too much for readers, I thought.”

Olivia suffers from recurrent bouts of ill health. Her short diary entry for “June 1814, Buitenzorg” reads:

I have been extremely unwell. The sickness came on in Batavia two days after the ball to mark victory at Leipzig, at which time I was seized by a return of my usual indisposition of the liver, which fickle organ did indeed collapse. I was subsequently conveyed here to Buitenzorg, where I lie now in bed and hope to recover.

She’d didn’t recover, passing away on 26 November, 1814. Raffles was devastated, and never really got over the loss. He married his second wife, Sophia Hull, in 1817. They set sail for Java, where Raffles was to take up his new appointment as the Governor-General of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu in Sumatra, Indonesia). The title sounded better than the reality. Bencoolen was an unhealthy, unprofitable backwater, and stepping ashore the newlyweds were far from pleased:

Tom, stalwart but dismayed, says he thinks Bencoolen must be more disregarded by The Company than any other unfortunate spot, and that tho’ he had not expected it to be as splendid as Java, he had been by no means prepared for the unhappiness and poverty which now meet him – he says this is without exception the most wretched place he ever beheld.

As rich as the characters, locations, and events upon which Milne could draw were, she faced a problem with the order of casting: the less interesting wife following the charismatic star. Milne overcomes this with fine writing, plotting and pacing, and with the climatic founding of Singapore being in the home stretch. Additionally, though Sophia at first seems rather dull and stuffy by comparison, she gradually wins you over with her steady courage and dignity, her loyalty, and her stiff upper lip in the face of great tragedy.

When I started Olivia & Sophia, I was looking primarily for something a bit more feminine than my usual no-girls-in-the-treehouse selections. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed the book. It’s beautifully and cleverly written, moving, entertaining and fascinating. When I finished the book, I immediately followed it up with some further reading on Raffles and his wives, including Sophia Raffles’ 1835 Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (available free online from archive.org).

Olivia & Sophia is published by Monsoon Books. It can also be purchased from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and various other retailers.

Rosie Milne lives in Singapore, where she is active in the literature scene. She blogs at the Asian Books Blog.