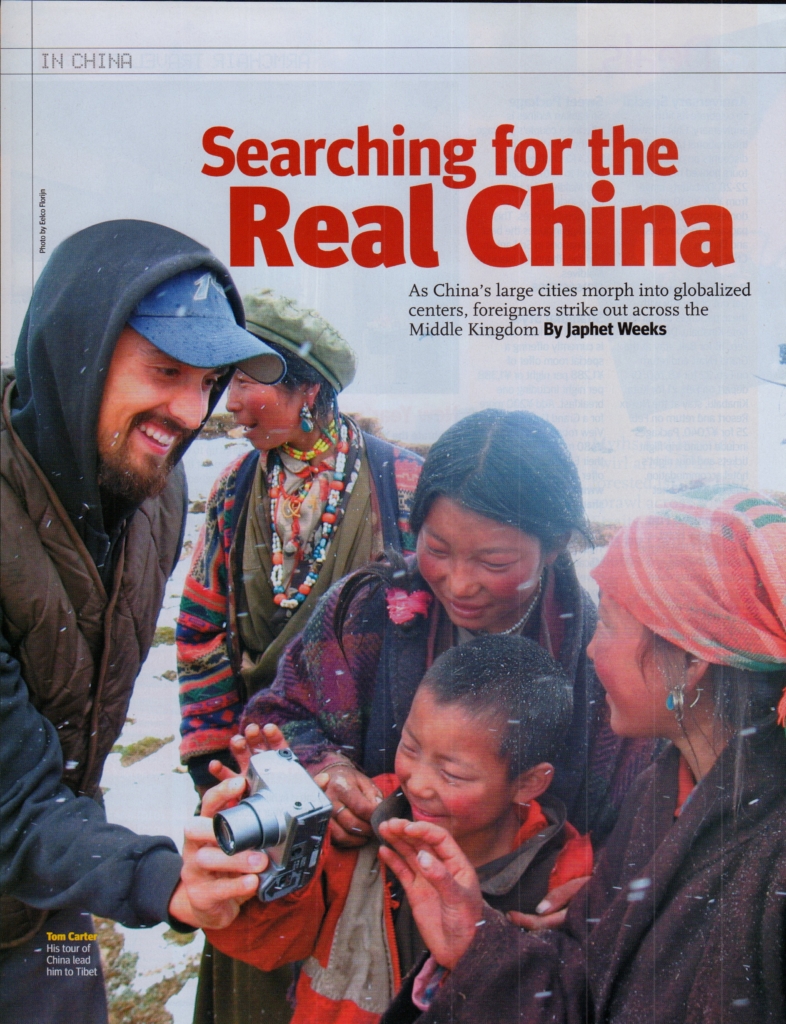

Talented American writer and photographer Tom Carter is one of the great characters of the expat tribe in China. I’ve always admired the way he throws himself into projects with the kind of tireless passion that makes the Energiser Bunny look lazy. When Carter did a photographic book on the people of China, he spent two years straight backpacking 35,000 miles across all of the country’s 33 provinces. When he edited Unsavory Elements, an anthology of expat writing on China, he didn’t settle for a manageable dozen or so entries, but compiled 28, including contributions from many big names such as Peter Hessler and Simon Winchester. I believe his latest work is his very best yet. It’s a remarkable true story about the exploits of friend and fellow American, the hapless Mathew Evans, who first went to China looking for romance. What ensued was an epic five-year adventure that would find Evans homeless, stateless, posing as a professor, imprisoned, deported, and caught in the middle of the 2014 Hong Kong protests. I recently spoke with Carter about An American Bum in China.

What was Evans’ reaction when you first mentioned the idea of a book?

On the contrary, it was entirely Matthew’s idea. After the 2014 Hong Kong protests, he ghosted me for a while. I think he felt betrayed by me for conspiring with his family to bring him home after all of his hardships. Then one day he suddenly pops up on my Skype saying he wants to write a book about his experiences. So I gave him some simple writing advice and suggested a few memoirs and travelogues to read for inspiration.

A few weeks later he asks me to read what he wrote. I remember it was like several pages of a solid wall of stream-of-consciousness text – not a single period or paragraph break – that would put Jack Kerouac to shame, and I’m all like “*sigh* nobody is ever going to publish this, pal.” And in classic, unfazed Matthew Evans, he just shrugs and says (as opposed to asks), “Okay, you write it then.” So I did.

What was the writing process? I assume it involved lots of Skype conversations and emails back and forth with Evans.

It was a whole week of all-night, long-distance Skype calls, just letting him ramble like a grandpa. Matthew’s best stories and all the cool little details that make Bum such a fun read come from him essentially talking to himself. Not to say that I didn’t sometimes lose my patience and snap at him to stay on topic. Many of his tales were so offbeat that I had to leave them out of the narrative just to keep it grounded and believable.

But as his biographer, a big advantage I had that most biographers don’t is that I was around for pretty much everything Matthew experienced over the course of his five years here, so I could corroborate what he recounted to me. I was his fact-checker and he was mine, if that makes sense. And I also had my own memories and interpretations of our friendship to fall back on as points of reference.

I love the structure of the book: the crazy beginning when Evans is crossing illegally into Burma on a mad money-making scheme, then the way the Iowa backstory is woven into the China adventure, and then the surreal ending with Evans at ground zero at the 2014 Hong Kong protests.

Thank you. Yes, I decided to write it in a fractured narrative structure because, in my research, I found many geopolitical parallels between the three main settings (Muscatine, Shanghai and Hong Kong), so it made more sense to disrupt the chronology of Matthew’s story arc in China with callbacks to his upbringing in Iowa.

On a symbolic level, I noticed that the color yellow continuously made appearances throughout Matthew’s life – the yellow daffodils of the Cancer Society, the official state/school colors of Iowa, and the yellow umbrellas of Occupy Hong Kong. And of course the whole Huckleberry Finn/Tom Sawyer allusion to Matthew’s and my friendship, not just because Matthew is the living reincarnation of Huck but because, believe it or not, my father named me after Thomas Sawyer.

These correlations give Bum a kind of organic narrative cohesion that made the burden of good story-telling easier on me. I don’t consider myself “a writer” and usually writing is a painful process for me, but this was one of the few times that I had a lot of fun with it, despite the fact that it took me 18 months from start to finish.

Can you explain the title An American Bum in China: Featuring the bumblingly brilliant escapades of expatriate Matthew Evans?

The second horror movie I ever saw, at age nine in 1982 on Betamax with my father, was An American Werewolf in London. That title has always stuck with me and finally I had the opportunity to pay homage to it, albeit in a cheeky way. I think that more China writers could use a good dose of self-depreciation. Everyone’s so pretentiously serious, calling themselves “China experts” and giving their books these highfalutin titles. Me, I’m just having a good time!

It certainly seems so with the illustrations. What’s the story behind those?

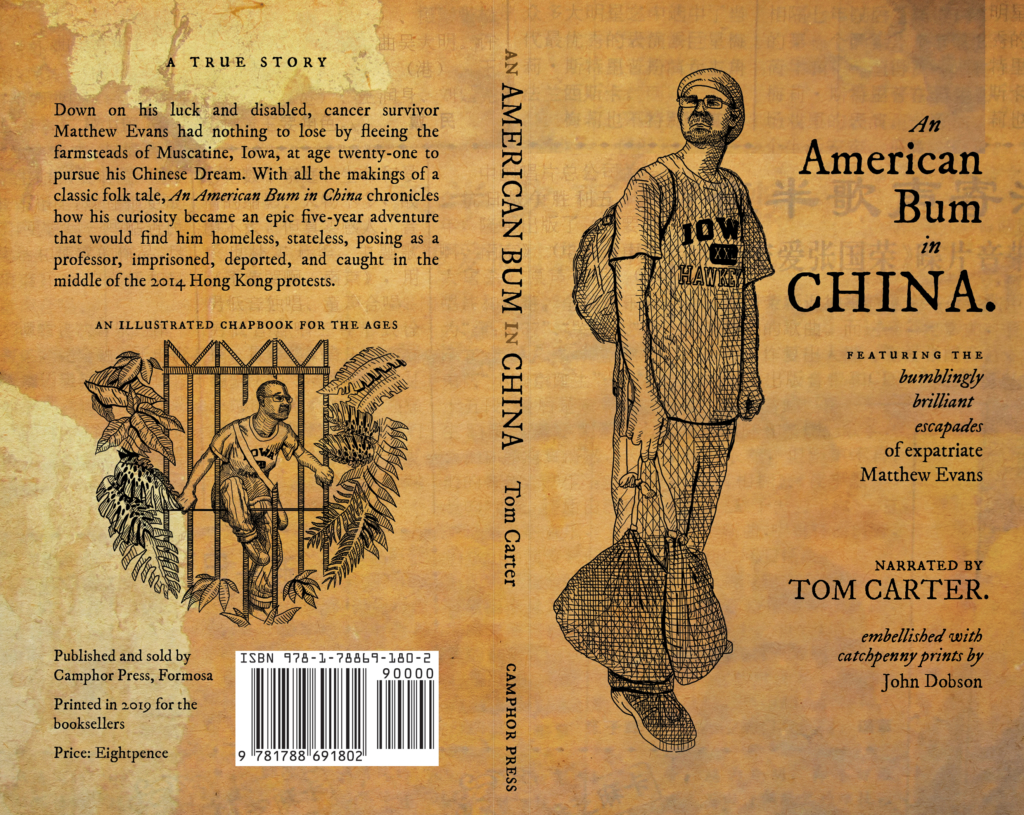

So the original concept of Bum was just a long-form essay, because of its brevity, but after getting rejected from literally every literary journal and long-form platform in existence (eat your heart out, Atavist!), one of my beta-readers encouraged me to self-publish it as a pulp dime novel. But Bum has more of a folk-tale feel, so I had this epiphany that it should be like a chapbook (illustrated folk tales from the 1600s) with accompanying art.

After deciding on that, I commissioned an artist named John Dobson to replicate the woodcut “catchpenny prints” style of the chapbooks, which have this rough, unsophisticated look that you never see anymore. There are 24 illustrations (about 2 or 3 per chapter), and we’d spend at least a couple weeks going back and forth for each via email, because we live in different countries. First he’d do the lines for one drawing, then after I was happy with it he’d work on the cross-hatching, then we’d move on to the next illustration. The whole process took another year. Dobson did brilliant work and I think his illustrations make Bum very different than other books on the market today.

And how about that old-fashioned cover?

The cover art was a collaborative process between me and Michael Cannings, who is one-third of Camphor Press. I knew that I wanted it to resemble a chapbook, with one of Dobson’s illustrations and old-school typesetting. To give it that soiled, antiquated texture, I went through my old photographs of China and found one of a newspaper from the 1900s that had been used as wallpaper in a dilapidated Shanghai lane house. Mr. Cannings then designed the cover and laid out all the illustrations, which took some trial-and-error to perfect. Again, a long process, but as you can see, well worth it.

Promoting books and moving copies has never been easy, but it seems that it’s noticeably harder than even half a dozen years back. Any thoughts on the publishing environment now compared to when you wrote CHINA: Portrait of a People (2008) and Unsavory Elements (2013)?

This is a topic that triggers me. At the time I’m answering these questions we’ve still got two weeks until launch (September 28, 2019), so maybe just maybe Bum’s fate isn’t as destined for permanent obscurity as it currently seems. But at this particular moment, I’m eating my bitterness about how closed-off Big Media is to indie publishers.

In the years between my first two books, Big Media was starting to warm up to the concept of independently published and even self-published books. An indie author like me with no agent and no PR rep could still get an actual response from a newspaper editor, who, after hearing your pitch, would either politely decline or say “sure, send it along.” There was no guarantee the paper would publish the review, but at least you had a fighting chance. This is how CHINA: Portrait and Unsavory both wound up getting coverage in a number of newspapers and magazines all around the world. No social or family connections, no money exchanging hands; just months and months and months of relentless cold-calling.

It’s been six years since Unsavory and the media and publishing landscape is now noticeably different. On top of all the dispiriting rejections I endured when first pitching Bum for publication, I’m finding that getting it reviewed is even harder. No polite rejections, not even a courtesy response to our pitch emails – just dead silence.

In their increasing efforts to control the global narrative, it seems that the world’s largest media conglomerates (just six companies now own pretty much every mass-market English-language print newspaper and magazine) and the Big Five publishers and their imprints (most which are controlled assets of those same six media companies) are no longer opening their doors to independently created works.

For Westerners writing about China, books that that were not conceived or vetted in a corporate boardroom are now categorically prohibited from being published by Big Publishing or reviewed by Big Media. I’d wager that this has to do with Corporate America’s growing codependency on the Chinese economy. Heaven forbid these mass media entities publish anything that might hurt the feelings of their new sugar daddies in Beijing (and I don’t say this disparagingly; the Party should be pleased with itself for finally forcing America to render and submit).

Yep, it’s a pretty bleak media and publishing landscape you paint. And I’m not going to push back, because I think what you’re describing is the unfortunate reality. However, do you see any bright spots in the world of publishing?

I predict indie presses will, at the end of the day, be the saving grace of the literary marketplace. The arrogance and exclusivity that pervades Legacy Publishing is not sustainable. Giving book deals to only those who are connected (through family or high society) and the new business model of boardroom-conceived books (where a bunch of executives are dictating their next best seller to a writer-for-hire) has resulted in a tragic decline in good ol’ fashioned story telling. All of their money can’t buy original ideas or creativity or experiences.

Has there been a single author on the New York Times Best Seller List in the past 20 years who rivals John Steinbeck or Pearl Buck or Gary Jennings or James Clavell? Nope, but they exist at the indie level. Here in China, some of the best stories being told in Chinese are online fiction authors who bypass the gatekeeping of traditional publishing by taking their writing directly to netizens. It’s brilliant, and you can be sure it’s got the Chinese publishing industry’s panties in a twist.

For foreigners writing about China, most independent publishers based in East Asia have open-door policies to ordinary fellows such as myself who do not have agents but might have a cool story to tell. I can personally attest to this, as I’ve had the privilege now of having been published by what I consider to be the Holy Trinity of English-language indie presses in East Asia: Earnshaw Books in Shanghai, Blacksmith Books in Hong Kong and Camphor Press in Taiwan.

Graham Earnshaw has lived in China since the 1970s and is now literally the oldest of Old China Hands here. Earnshaw Books is also now, I believe, the last-standing foreign-owned publisher in the Chinese mainland, which is a testament to Graham’s deep knowledge of the Chinese people, their culture and their politics. This was why I specifically asked Graham to publish Unsavory Elements.

Blacksmith Books is operated out of Hong Kong by Pete Spurrier, who has local street-cred for being one of the last remaining book publishers to withstand the closures or disappearances that have caused the HK book publishing industry to collapse in recent years. Back in ‘08, when he was just starting up, Pete took a huge financial risk on my 630-page book of China photography when nobody else would; fortunately, it paid off for us both, commercially and critically.

Indeed, the P.R.C. has been making it increasingly difficult not only for Hong Kong publishers, but also for all international publishers in general.

The issue is that, because so many Western publishers print their books in the Chinese mainland (to cut costs), several months ago the Party, as part of its continued crackdown on foreign influence, issued an edict that all foreign books printed here must comply with Beijing’s censorship standards, which are of course notoriously strict. If they don’t like your book – whatever the subject matter, whatever the language – it’s not getting printed in China anymore.

As I touched on above, most major American publishers will self-censor if it pleases the Party, and authors who crave that Big Publishing stature will let them. But if you are an author who minds having your manuscript given the equivalent of a forced sterilization, the best alternative is, in my humble opinion, Camphor Press, who are based in Taiwan and thereby defiantly free to print whatever their renegade hearts desire – including a novel about a talking Communist phallus. Seriously.

You are, I presume, referring to Arthur Meursault’s Party Members?

Yes sir, the must-read China book of this decade. For those who haven’t heard of it, it’s a foreigner-penned hybrid of Chinese “officialdom lit” and the “ultra-unreal” genre (though to Meursault’s credit Members was written before either of those genres became things). The reason why so many reviewers and influencers in our little Sino-twitterati scene loathed it and refused to even mention it as a hate-read is exactly why I loved it: it is mean and funny and vile and brilliantly provocative. It’s the Salò or 120 Days of Sodom of China writing.

It will make you sick to your stomach, and not just because it is graphic but because so much of it is based on truth. If you think that Meursault is in any way exaggerating the personalities and lifestyles of low-level Communists cadres, then you probably haven’t lived in China. Xi should have endorsed Party Members and forced all 90 million members of the Party to read it, because it portrays perfectly the type of corrupt “flies” that his infamous anti-corruption campaign has targeted. I feel it is destined to become a cult classic, especially if it ever gets translated into Chinese.

There are some strange rumors out there about you and Meursault. Want to clear them up?

Heh, I’m not Arthur Meursault, as some netizens on WeChat have speculated. We’ve never even met. Nor was I paid in hookers to promote Party Members, as another rumor on Reddit claimed. In fact, I heard but can’t verify that Meursault co-owns with his gay Chinese lover a KTV brothel in Changsha, but I never got an invite.No but seriously, Members is a big reason why I sought out Camphor Press to publish Bum, and I was deeply honoured when they agreed.

You’re a bit of a maverick among China writers. What’s the English-language literary scene like in Shanghai?

Perhaps not as prominent as Beijing’s, but I think it’s something special, though I don’t expect it to last much longer under the current regime. Shanghai’s literary scene as we know it today is very different than Beijing’s in that its roots are in the emergence of the Haipai (“East meets West”) culture of the 1920s and ‘30s, which gave birth to some very radical local writers such as Lu Xun and of course Eileen Chang, who I adore.

For a few years I worked right next door to Chang’s old residence (Eddington House) where she penned her most acclaimed stories, so I fancy that I channeled some of her spirit while writing Bum. We also have the Shanghai Literary Festival at M on the Bund, where I am proud to have launched all of my previous books to tremendous turnouts. And Shanghai is home to Graham Earnshaw, who I mentioned above. So yeah, Shanghai has played a very important part in my creative output this past decade; whatever sociopolitical turmoil is destined for China next decade, I will always consider it my literary home.

Readers are going to wonder what happened to Matthew Evans after he got back to the States. Where is he now and what is he doing?

If I had to guess, Matthew is probably back in Hong Kong as we speak, getting beaten with a bamboo stave by the white shirts. But really, even if I knew, which I don’t, he is completely off the grid and has this thing about not telling me what he’s up to until after the fact.

And what about yourself? What’s next for Tom Carter?

Right now I’m feeling like An American Bum in China might be my swan song in the publishing world. I felt passionate enough about telling Evans’ story that I was willing to put myself through all the rejections and, worse, the mute silence of the media, but the other half-dozen half-finished books sitting on my hard drive probably won’t ever see the light of day. Sorry to disappoint my four fans.

Just pre-launch jitters I think, Tom. The promotional phase of indie publishing is always painful, so I don’t blame you for wanting this to be your last. But from what I’ve read, I’m sure Bum will do very well.

* * *

An American Bum in China is published by Camphor Press.

Check out Tom Carter’s profile page on Amazon.